“(Erek) Culbreath said, ‘According to the state of Florida, you are almost twice as likely to get attacked by an alligator than by someone with a conceal-and-carry permit.'”

“(Erek) Culbreath said, ‘According to the state of Florida, you are almost twice as likely to get attacked by an alligator than by someone with a conceal-and-carry permit.'”

…

We find the statement has an element of truth but ignores other information that would give a different impression. So we rate it Mostly False.”

—PolitiFact Florida, from a March 23, 2015 fact check of a statement from a spokesperson for Florida Students for Concealed Carry

Overview

PolitiFact Florida’s examination of a statement about concealed-carry gun permits affords us a fine opportunity to examine and critique PolitiFact’s fact-checking methods.

The Facts

On March 16, 2015, Florida’s Senate Higher Education Committee conducted a hearing to consider testimony on two proposed bills. The committee spent most of its time on the second bill, concerning licenses to carry concealed weapons. That bill would amend the concealed carry statute, allowing permit holders to carry concealed weapons on college and university campuses. Testimony on that bill, SB 176, drew the attention of PolitiFact Florida:

“According to the state of Florida, you are almost twice as likely to be attacked by an alligator than by someone who happens to carry a conceal-and-carry permit, and that was a study over the first 10 years of the conceal-carry law in Florida,” said Erek Culbreath, president of Florida Students for Concealed Carry, a group that advocates for concealed carry of firearms on all the campuses.

Are gator attacks twice as common as attacks by someone who has a conceal-and-carry permit? We went in search of the evidence.

In addition to searching for the evidence that gator attacks outnumber attacks by a person with a conceal-and-carry permit, PolitiFact Florida considers whether the comparison makes sense.

We’ll look at whether PolitiFact’s examination of those issues makes sense.

We find two major faults with PolitiFact Florida’s handling of this fact check. First, PolitiFact Florida disregarded Culbreath’s stipulation that his claim about alligator attacks applied to the first 10 years of Florida’s concealed carry law. Second, PolitiFact Florida found Culbreath’s underlying argument reasonable and his statistical statement close to the truth yet ruled the statement “Mostly False.” We’ll address those major issues and a handful of minor issues in the three sections that follow.

Ten Years

While Erek Culbreath in his testimony emphasized his comparison of gun attacks to alligator attacks applied to a 10-year period after the enactment of Florida’s concealed carry law, PolitiFact Florida did not fact check the claim for that time period. Checking what Culbreath said in context was too difficult, if not impossible:

We were unable to obtain more details about whether those 168 assaulted someone or misused the gun in some other way. We also couldn’t isolate data just for 1987 through 1997 to provide a decade comparison to the alligator bites.

But overall, alligator bites happen more often than the revocation of gun permits for misuse of firearms.

We think it improper for a fact checker to disregard the context of a statement simply owing to the greater ease of doing a fact check of the statement taken out of context. Words matter, don’t they?

PolitiFact Florida ran into a difficulty with the statistic used to count attacks by concealed carry permit holders. The factoid uses permit revocation caused by improper use of a firearm to estimate attacks by concealed carry permit holders. The measurement is far from perfect. One of the experts PolitiFact Florida cited noted that a permit holder might get away with an attack without having the permit revoked. We note that a permit holder might have a permit revoked for committing a crime involving a weapon without attacking anyone.

Worse for PolitiFact Florida, it could not find a year-by-year record of permit revocation. Without knowing the number of revocations over the first 10 years of the concealed carry law, which went into effect in 1987, a fact checker cannot verify Culbreath’s claim.

We’re not sure how hard PolitiFact Florida tried to uncover the statistics. Though the lack of data available directly from the state government makes things difficult, we pieced together a reasonable approximation.

Gun advocate John R. Lott researched permit revocation in his 1998 book “More Guns, Less Crime.” Lott’s book notes 72 revocations in Florida, citing the website of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services:

Between October 1, 1987, when Florida’s “concealed-carry” law took effect, and the end of 1996, over 380,000 licenses had been issued, and only 72 had been revoked because of crimes committed by license holders (most of which did not involve the permitted gun).

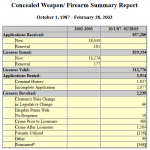

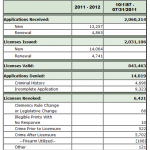

We found webpage snapshots of Lott’s source at the Internet Archive. One was old as February 2003 and another as recent as June 2012. The number of revocations due to crimes climbed steeply as Florida issued increasing numbers of licenses.

These resources give a picture of a rapidly changing set of statistics, particularly if we conclude from Lott’s book that by 1996 only 72 concealed carry licenses were revoked based on committing a crime. A little over six years later that number increased to 1,584. We infer that the number of revocations for crimes with a firearm also experienced a spurt, for Lott’s reporting suggests that number was under 36 at the end of 1996. By 2003 the number jumped to 156.

It’s worth noting the stability of the “firearm utilized” statistic between 2003 and 2011.

It appears concealed carry advocates first compared alligator attacks to crimes connected to permit revocation, regardless of whether a firearm was involved. As the number of revocations for crimes grew, advocates shifted to talking about the number of revocations associated with crimes involving a firearm. That number continued to run lower than the number of alligator attacks through 2010 when, as PolitiFact Florida notes, the state stopped tracking reasons for revoking the permits.

Alligator Attacks

We have pretty good evidence that less than 36 Florida concealed carry licenses were revoked for crimes involving a gun between 1987 and 1996. Now we’ll try to estimate the number of alligator attacks in the ten years after 1987 to assess the strength of Culbreath’s claim. But first we’ll review what PolitiFact Florida found:

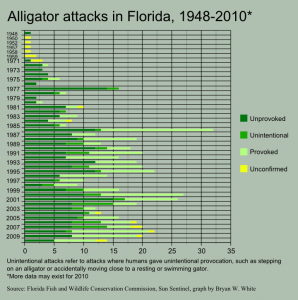

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has documented the number of alligator bites on people between 1948 and November 2013 for a total of 357 bites. (For the record, that is strictly bites by alligators and not crocodiles, which are rare.)

We took a closer look at the alligator bite statistics through a database hosted by the Sun Sentinel. We had trouble matching our analysis of the database to the chart PolitiFact used as its source. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission included unconfirmed reports and unintentionally provoked attacks in its numbers. We omitted from our numbers unconfirmed reports and cases where investigators thought no attack occurred. We counted a total of 337 attacks from 1948 through 2010, with 101 of those occurring in the 10 years since Florida passed its concealed-carry permit law (1988-1997). Our count over the 10-year period was four higher than the 10-year total from the FWC.

For the 10-year period Culbreath specified, we judge it likely that the number of alligator attacks was more than twice the number of revocations of concealed permits for crimes involving a handgun.

For the 10-year period Culbreath specified, we judge it likely that the number of alligator attacks was more than twice the number of revocations of concealed permits for crimes involving a handgun.

While we note that revocation of permits for improper use of a weapon rose sharply at some point in the 1990s, chances are not enough of a bump occurred in 1997 to undermine Culbreath’s claim. The number for 1998 would have to represent an increase of a least 42 percent over the total number in the preceding nine years. The number does rise sharply between 1998 and 2003, but we have no good reason to expect a disproportional rise in 1998.

PolitiFact’s Wrongs

Though PolitiFact Florida found evidence supporting and not contradicting Culbreath’s statistics, his statement received a “Mostly False” rating.

What information was ignored that would give the impression that alligator attacks did not occur twice as often as attacks by concealed carry permit holders during the first 10 years of Florida’s concealed carry permit law? We don’t see anything of the kind in PolitiFact Florida’s fact check. The statistics have one drawback in terms of reliability: They’re difficult to verify with certainty. In effect, PolitiFact Florida blames Culbreath for ignoring information PolitiFact Florida did not find.

Needless to say, that’s not fact checking.

PolitiFact Florida went beyond assessing Culbreath’s facts, looking also at his underlying argument. PolitiFact Florida delegated most of that task to experts it interviewed. That approach was wrongheaded in this case.

James Alan Fox, criminology professor at Northeastern University, said comparing alligator attacks to attacks by holders of concealed carry permits was silly.

Adam Winkler, a UCLA law professor and expert on the second amendment likewise had trouble taking the comparison seriously.

Fox and Winkler both made attempts to illustrate the absurdity of Culbreath’s comparison.

A third expert, Harvard’s David Hemenway, likewise offered reasons why the comparison was problematic. For example, Hemenway said the number of permit revocations would not necessarily record every instance of a permit holder misusing a firearm.

PolitiFact Florida’s fourth expert covered himself in glory with his response:

Florida State University Professor Gary Kleck said that the comparison to gator attacks was likely used to indicate how rare gun crimes by carry permit holders are. “It could just as easily been something else that’s really rare, like death from meteor strikes or midair aircraft collisions. The point is merely that these things are extremely rare,” he said.

We think Kleck is obviously correct, and we hasten to point out that the brilliance of his response probably doesn’t rely on his expertise in criminology and criminal justice at all. He’s just speaking common sense. People commonly use these types of comparisons. If somebody claims they saw a UFO as big as a football field, is it helpful for some expert to explain how the football field isn’t appropriate at all for either atmospheric flight or interstellar travel? Of course not. The point is the size comparison, just as the alligator bite comparison emphasizes frequency.

Fact checkers shalt not, for purposes of judging claims of fact, place experts on a pedestal unrelated to their expertise.

Conclusions

PolitiFact Florida concluded Culbreath’s claim was “Mostly False”:

We don’t have data on attacks committed by people with conceal-and-carry permits. The gun data is based on an approximation using permit revocations that may or may not accurately reflect the number of “attacks.” Also, the data is 10 years old.

That said, these statistics, imperfect as they are, do support the notion that both kinds of attacks are uncommon. Whether this is a valid argument in favor of the bill is in the eye of the beholder. We find the statement has an element of truth but ignores other information that would give a different impression. So we rate it Mostly False.

PolitiFact Florida makes a valid point that the permit revocation stats can only offer a very rough approximation of attacks by concealed carry permit holders. On the other hand, the complaint about 10-year old data counts as irrelevant and inaccurate. It’s irrelevant because Culbreath’s claim deals with 1988-1997, which was more than 10 years ago. It’s inaccurate because the state of Florida continues to update its records on the revocation of permits for improper use of a firearm, at least up through 2010. By our count, 2010 was less than 10 years ago.

PolitiFact Florida finds the statistics support the point that attacks by concealed carry permit holders occur rarely. So Culbreath’s underlying point was right. We showed that Culbreath’s statistics were probably correct. So with the statistics likely correct and an accurate underlying point, PolitiFact Florida says Culbreath’s statement “has an element of truth but ignores other information that would give a different impression.” We wonder what specific information the team at PolitiFact Florida had in mind, for we see no “other information” in the fact check that should reasonably cause Culbreath’s audience to question either his statistics or his conclusion. There’s only PolitiFact Florida’s failure to find more information supporting Culbreath’s claim.

Summary

PolitiFact Florida failed to handle facts with care, and ended up judging a straw man version of Erek Culbreath’s claim.

“(Erek) Culbreath said, ‘According to the state of Florida, you are almost twice as likely to get attacked by an alligator than by someone with a conceal-and-carry permit.'”

PolitiFact quotes Culbreath accurately, but leaves out his stipulation that the comparison covers only the first 10 years of Florida’s concealed carry statute. PolitiFact Florida creates a straw man fallacy with its omission of context.

“We find the statement has an element of truth but ignores other information that would give a different impression.”

Taken as statement of fact and not opinion, and as a summary of PolitiFact Florida’s work, we find no evidence at all of “other information” that ought to lead any reasonable reader to conclude Culbreath was wrong on the facts or with his underlying argument that concealed carry permit holders only rarely use their guns to attack others.

Additional Note

We considered the possibility that fact checkers, including ourselves, failed to consider that Culbreath referred to any type of attack by a concealed carry permit holder. An attack with a battle axe counts as an attack, after all. However, the context of Culbreath’s claim argues he was talking about attacks with a gun. Otherwise the critic ends up assuming at the outset that Culbreath offered completely inadequate evidence in support of his claim. It’s proper to interpret Culbreath charitably.

References

Sherman, Amy. “Are Alligator Attacks More Common than ‘attacks’ by Those with a Gun Permit in Florida?” PolitiFact Florida. Tampa Bay Times, 23 Mar. 2015. Web. 02 Apr. 2015.

“3/16/15 Senate Higher Education Committee.” The Florida Channel. The Florida Channel, 16 Mar. 2015. Web. 02 Apr. 2015.

“Concealed Carry Revocation Rates by Age.” Crimepreventionresearchcenter.org. Crime Prevention Research Center, 04 Aug. 2014. Web. 02 Apr. 2015.

“Concealed Weapon/ Firearm Summary Report October 1, 1987 – February 28, 2003.” MyFlorida.com. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, 2003. Web. 02 Apr. 2015.

“Concealed Weapon / Firearm Summary Report October 1, 1987 – June 30, 2012.” MyFlorida.com. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, 2012. Web. 02 Apr. 2015.

“Myth #6 – “Concealed Carry Reform Will Take Us Back to the Wild West!”” Buckeyefirearms.org. Buckeye Firearms Association, n.d. Web. 02 Apr. 2015.

Lott, John R. More Guns, Less Crime: Understanding Crime and Gun-control Laws. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1998.

Lott, John. “Fla. Has 800,000 Concealed Permits – Revoke Rate Miniscule.” Newsmax. Newsmax Media, Inc., 26 Apr. 2011. Web. 02 Apr. 2015.

Lemonick, Michael D. “Death by Alligator.” Time. Time Inc., 21 May 2006. Web. 02 Apr. 2015.

Williams, Dana, and John Maines. “Database: Alligator Attacks in Florida.” Sun-sentinel.com. Sun Sentinel, n.d. Web. 02 Apr. 2015.

“Alligator Bites on People in Florida.” Myfwc.com. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Nov. 2013. Web. 02 Apr. 2015.