Last month we asked the director of the International Fact-Checking Network, Alexios Mantzarlis, to give the strongest comprehensive case in favor of fact-checking organizations using rating systems.

We asked because most fact-checking organizations use some sort of sliding scale rating system. Given the popularity of the practice we felt it was beneficial to encourage the IFCN to publish a rationale in support of one of the common practices among fact checkers.

Mantzarlis offered a good answer to our question, acknowledging the limitations of sliding-scale while making a plausible positive case that such ratings help readers more easily grasp the gist of the fact check.

But we also found his answer a bit troubling.

The answer was not troubling for the sake of its content. We found it troubling because we saw only a little of Mantzarlis’ reasoning in the answers other fact checkers gave when asked why they used rating systems.

In “Everyone Hates the Referee: How Fact-Checkers Mitigate a Public Perception of Bias,” former PolitiFact intern Allison Colburn asked a number of fact checkers questions about the use of rating systems.

Angie Drobnic Holan (PolitiFact editor)

When asked why PolitiFact uses a rating system, Holan said the driving reason stemmed from the project’s focus on structured data.

Well when we conceived of PolitiFact, we started off thinking about, and because the site is so highly structured, it made sense for us to have ratings because we wanted to be able to sort statements by relative accuracy. You can’t really sort and analyze findings without having some sort of ratings system, even if it’s not even if it’s not set as a literal rating.

Colburn asked Holan a terrific follow-up question. Why the interest in the structured data in the first place? Holan answers that despite the unscientific nature of the process it allows people to draw conclusions:

Well any kind of journalism, when you apply structured data, it gives you more dimensions for reporting and analysis. So it’s like if you just have a database of news stories, it’s really hard to spot trends or summarize. And we wanted to be able to like pull up all the statements on a given topic or on or that a given person said. And being able to look at the ratings gives you a quick snapshot of relative accuracy. Now I think some people take the ratings too far in what they think we’re trying to say, because we don’t fact-check a random sample of what any one person says or a random sample on any one topic. So some of our audience sees this as an opportunity for us to have biases and bring our biases in, but that’s not what we’re intending.

PolitiFact, according to Holan, uses a rating system to allow people to draw conclusions from unscientific data, specifically its aggregated ratings.

Mantzarlis warned about the misuse of aggregated ratings when he addressed our question.

Glenn Kessler, the Washington Post Fact Checker

Kessler’s response led with his acknowledgment that a rating system serves as great marketing gimmick.

Because it’s a great marketing gim[m]ick. (laughs) I mean, it’s a ps[eu]do-scientific, subjective thing. It’s an easy, simple way for readers to get a sense of the bottom line of the fact-check. I do know there are people who all they do is just go straight to the Pinocchio, and they don’t read the fact-check. That’s a problem. We spend a lot of time on the fact-check.

Kessler, as did Mantzarlis, emphasized the utility of the rating system for communicating the gist of the fact check to readers.

And another aspect of his reply caught our attention. Kessler hints that the subjective ratings help fact checkers achieve greater objectivity:

I’m a big fan of the rating system. I think it’s a good way to keep track. I have to say, I’ve done this for almost seven years. It allows me to keep in mind how I rated things before, and to be consistent. I think that’s a very helpful tool.

We think the notion that subjective ratings help fact-checkers achieve greater objectivity deserves a great deal of skepticism.

Linda Qiu, The New York Times (former PolitiFact fact checker)

Though The New York Times’ fact checker does not use ratings and Colburn did not ask Qiu for a case in favor of ratings, Qiu offered up a rationale during the course of her interview.

“I think the benefits of having a rating system is that it’s much more digestible,” Qiu said. “It is also a really good way of marketing the fact-checks.”

Reconciling Mantzarlis With the Other Fact Checkers

A comprehensive case for using a sliding scale rating system ought to include the entire positive and valid argument for that type of rating system.

If its role as a gimmick drawing readers counts as positive and valid, then that reason ought to have its place in the argument for a rating system. We do not object to including audience attraction as part of the positive case for rating systems. In fact, we were surprised to find it missing from the answer Mantzarlis gave us.

Mantzarlis and the fact-checking community seem to end up on the same page in seeing a positive role for rating systems in providing a valuable summary for readers. We view that argument skeptically and applaud Mantzarlis’ call for supporting research.

The Objectivity Problem

The case against rating systems has always stemmed from the inherent subjectivity of sliding-scale systems. And until sliding-scale rating systems base their ratings clearly and directly on objective and verifiable findings, we can rightly dismiss notions that such rating scales help fact checkers achieve objectivity in their work.

Applying subjective rating scales “consistently” without an underlying objective basis for the rating counts merely as giving readers the impression that an underlying basis of objectivity exists. Instead of the facts determining the rating, a “consistent” subjective rating determines (subjectively) which facts correspond to that rating, which then serves as the pattern for future ratings.

Fact checkers may achieve consistency with that method, but objectivity does not result. The result, at best, is an appearance of the objectivity one would expect from a rating system based on objective and verifiable indicators.

Put another way, inconsistent ratings are consistent with subjective ratings. Inconsistent ratings are not consistent with objective ratings. Taking steps to make subjective ratings look objective counts as deceit.

The Case in Favor of Sliding Scale Rating Systems

We hold that the strongest argument in favor of sliding scale rating systems rests on their ability to draw readers. Successful gimmickry draws readers, and fact checks with no audience have little power to inform.

Secondarily, rating systems may help readers understand and retain fact check information. Unfortunately that point in favor thus far lacks convincing research in support.

The Case Against Sliding Scale Rating Systems

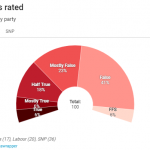

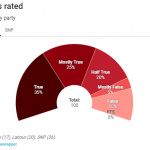

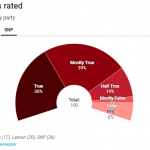

Aggregating the results of subjective sliding scale ratings and presenting such results to readers as useful data counts as deception. For example, earlier in 2018 the Ferret, a fact checker in Scotland, presented its aggregated ratings by party as a useful guide to its readers:

No good reason exists to take such charts as representative of party truthfulness. Yet fact checkers often make use of aggregated ratings as though the opposite is true.

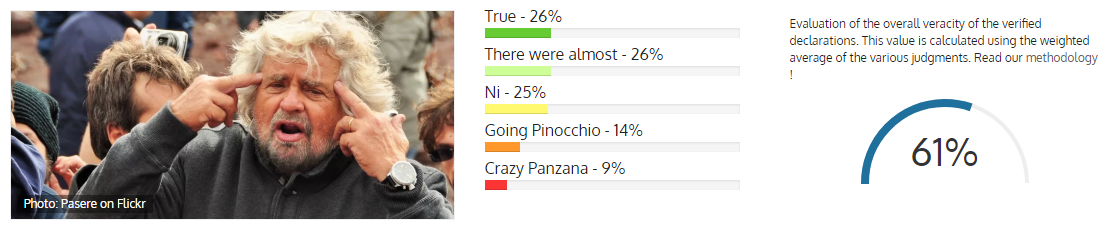

Even Italy’s Pagella Politica, which Mantzarlis offered as an example of an organization offering fair warning to readers, relegates the caveats to a drill-down page. This is what readers saw (Google translated) if they did not bother to click the drill-down URL:

We don’t think “Read our methodology!” counts as much of a warning unless quite a bit is lost in translation. The organization should offer readers the basic reason for the importance of reading about the method. The drill-down page does a great job of the explaining the problem, even via the Google translation, but readers should have the gist of that content on the referring page. Something like “We caution readers against drawing conclusions from these graphs and percentages. Read the description of our methodology to see why” would fill the bill.

The Verdict

Zebra Fact Check regards sliding-scale gimmickry as acceptable if organizations transparently and consistently explain to readers their limitations. We see far too little of that from fact-checking organizations. We would like to see the IFCN issue guidelines to fact checkers in line with what its director described as the strongest rationale for rating scales.

We prefer fact-checking without a rating system, unless that rating system bases its presentation directly on concrete aspects of claim analysis (as ours tries to do).