“From what we know now, [Jason] Furman’s statement stands up to scrutiny. He earns a rare Geppetto Checkmark.”

“From what we know now, [Jason] Furman’s statement stands up to scrutiny. He earns a rare Geppetto Checkmark.”

—Glenn Kessler the Washington Post Fact Checker, Nov. 11, 2013

Overview

Furman’s statement needs more scrutiny.

The Facts

The Washington Post Fact Checker, Glenn Kessler, posted a fact check of a White House economic adviser on November 11, 2013. The adviser, Jason Furman, serves as chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers. Furman said (as reported by Kessler):

“If you look at the biggest thing that are cutting our deficit over the medium and long run, it’s actually the Affordable Care Act, which is, you know, by bringing down the cost of health care, that doesn’t just help our economy, it helps bring our deficit down.”

The above, by Kessler’s assessment, earns the “rare Geppetto Checkmark” denoting “‘the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.’”

Analyzing the Rhetoric

To assess Kessler’s accuracy we need to test Furman’s statement for evidence of a failure to tell the whole truth and nothing but. We find a minor strike against Furman right away, as his answer dodges the question from MSNBC host Chris Jansing:

CHRIS JANSING

You know what the Republicans would say, uh, the effect of the sequester has been terrific on the debt, and in fact they would take a lot of credit for what we’re seeing right now in debt reduction. What would you say?JASON FURMAN

You know, if you look at the biggest thing that are [sic] cutting our deficit over the medium and long run it’s actually the Affordable Care Act, which is, you know, by bringing down the cost of health care, that doesn’t just help our economy, it helps bring our deficit down.

Jansing’s question leads directly to the big problem with Furman’s answer. She mentions what we’re seeing now in deficit reduction (though she wrongly called it the debt). The deficit is coming down. Part of that comes from the tailing off of stimulus spending, part of it comes from the repayment of bailout loans and part of it comes from the sequester cuts. Slowed growth of Medicare costs also contributes. That’s the short-term picture, but  Furman answers in terms of the medium and long run. But in the medium and long run the deficits are going up, not down. So Furman’s answer makes use of one of the classic political deceptions: calling a slowing in the growth of the deficit a cut to the deficit.

Furman answers in terms of the medium and long run. But in the medium and long run the deficits are going up, not down. So Furman’s answer makes use of one of the classic political deceptions: calling a slowing in the growth of the deficit a cut to the deficit.

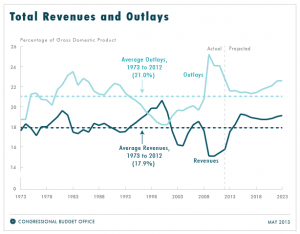

The CBO graph to the right illustrates the coming return to increasing deficits. When the line representing outlays is higher than the one for receipts and the space between is increasing, the deficit is likewise increasing.

Despite what Furman says, nothing is cutting the federal budget deficit in the medium to long run. It’s going up.

But Furman still has a point that the ACA is slowing deficit growth, right?

The structure of the ACA directly contributes to confusion about its effect on the budget. The law mandates certain expenses, such as those associated with providing Medicaid to a larger population. But the law also features various tax increases, such as a 10 percent excise tax on ultraviolet indoor tanning services. The ACA therefore affects both outlays and revenues.

Why is it important that the ACA increases outlays and revenues? Because the increase in outlays eats up the bulk of the revenues, and makes the consumed revenues unavailable for deficit reduction. It’s an issue of opportunity cost, to use the economists’ term. Every occurrence that changes the ACA’s effect on outlays or revenues affects, in turn, the ACA’s effect on the budget.

Kessler tested Furman’s claim using estimates from the Congressional Budget Office, often viewed as a type of gold standard by journalists and fact checkers because of its staunch non-partisanship and consistent methodology, using “current law” as a baseline for its future projections.

Unfortunately, politicians have learned to play the CBO against the public by crafting bills such as the ACA. Take the “doc fix,” for example. A law on the books since 1997 would strictly limit the growth of Medicare reimbursement rates for doctors. Congress intervenes every year or so to make sure doctors receive enough pay to keep them serving Medicare patients. The CBO’s methods require it to ignore in its projections Congress’ expected future actions since those do not count as current law. So a bill like the ACA can force the CBO into painting an unrealistic picture of fiscal benefit around a proposed law.

In 2010, the year the health care reform law was enacted, the CBO did its projections for the law’s impact on the budget. But things have changed. The administration dropped all attempts to implement the cost-saving CLASS program after declaring it fiscally unsustainable. Some states took advantage of a Supreme Court ruling to opt out of expanding Medicaid coverage. The administration delayed enforcement of the ACA’s employer mandate, releasing employers from the law’s penalties for failing to provide insurance to employees.

These types of changes add up, and a July 2013 article in Investors Business Daily estimated that over its first 10 years the health care law will slightly increase the budget deficit. We don’t ask readers to accept that estimate uncritically, but simply to recognize the solid foundation for taking the CBO’s 2010 projections as unreliable.

Kessler:

The information that follows is based mostly on estimates by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, some of which are long-range estimates subject to many variables. Reasonable people might disagree on whether these estimates are correct — skeptics might argue that the long-term cost of “Obamacare” is undercounted–but it’s the best that we have at the moment.

The IBD study is newer, takes into account at least some of the variables that have unquestionably changed since the CBO did its analysis and bases its numbers on information from the CBO and the Government Accountability Office. The IBD study is arguably the best we have at the moment.

Kessler:

Reductions in Medicare spending were responsible for a large part of the deficit reduction in 2013; the law will not be fully implemented until 2014.

Medicare expenditures continued to rise in 2013. Medicare spending was not reduced, but the growth of Medicare spending was reduced. Kessler goes on to credit the health care law with 10 percent of 2013’s deficit reduction. We’re not sure how he justifies that figure, but we note that the bulk of any deficit reduction from the law comes from its tax increases.

The long, short and medium of it

The reduction in the deficit for 2014 probably owes more to the sequester than to the ACA, and it’s worth noting that Furman emphasized the effects of the ACA based on lowering medical costs. There’s scant evidence the ACA bears principal responsibility for lowering medical costs. The law’s tax increases serve as its primary tool in lowering deficits.

Over a 10-year run, the sequester cuts outperform the ACA by the CBO’s numbers, though Kessler somehow avoids giving the point any emphasis. He says the sequester lowers (the growth of) the deficit by $100 billion per year. Kessler doesn’t tell his readers the peak effect from the health care law during that 10-year run occurs in 2022 with a $44 million deficit reduction. He omits any comparison of the respective laws’ first 10 years or so and starts talking about the long-term comparison.

In the long term, the ACA finally achieves an advantage. The CBO estimates a deficit reduction of 0.5 percent of GDP from 2023-2032. In contrast, the sequester law terminates after 2022 and has no long-term effect on deficits.

To us, extolling the superior deficit effects of the ACA during the time period when the sequester no longer operates seems like a classic apples-to-oranges comparison.

Summary

“From what we know now, Furman’s statement stands up to scrutiny.”

![]()

Any real scrutiny Kessler brought to bear tends to undercut Furman’s claim. Furman led off by dodging a question posed by his interviewer. Furman gains when Kessler ignores his own caveats about the CBO’s projections. Furman then achieves his greatest triumph in getting Kessler to accept as relevant a long-term comparison between the ACA and the sequester after the latter bill sunsets.

We accept it as trivially true that once the sequester sunsets the ACA will do more to cut the growth of the deficit. Furman’s other claims, contrary to Kessler’s judgment, wither under scrutiny.

If that’s worth a Geppetto Check Mark maybe we should throw in a Nobel Peace Prize for good measure. We’re not rating the truth of Kessler’s claim because of the uncertainty involved for the medium run comparison, but we’re charging Kessler with a one-sidedness fallacy for not noting the IBD assessment. It was published well before Kessler did his fact check, and even if he did not trust its conclusion that report warrants mention.

References

Kessler, Glenn. “What Will Have a Greater Impact in Reducing the Deficit: The Sequester or ‘Obamacare’?” The Fact Checker. The Washington Post, 11 Nov. 2013. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Furman, Jason. “What Shutdown? Jobs Soar in October.” Interview by Chris Jansing. MSNBC. NBC Universal, 8 Nov. 2013. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Aizenman, N. C. “Medicare ‘doc Fix’ Debate in Congress Less Predictable This Year.” Washington Post. The Washington Post, 23 Dec. 2011. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Blom, Barry. “How the Actual Federal Budget Results for 2013 Compared With CBO’s May 2013 Estimates.” CBO. Congressional Budget Office, 6 Nov. 2013. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

“Monthly Budget Review—Summary for Fiscal Year 2013.” CBO. Congressional Budget Office, 7 Nov. 2013. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Carey, Mary Agnes. “FAQ On Medicare Doctor Pay: Why Is It So Hard To Fix?” Kaiser Health News. Kaiser Family Foundation, 27 Feb. 2013. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

“Sebelius On The CLASS Act: ‘I Do Not See A Viable Path Forward’” Kaiser Health News. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 15 Oct. 2011. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Palermo, Dan. “The PPACA and the Federal Deficit: What Is the True Effect of the Legislation?” Annals of Health Law 20.Spring (2011): 191-99. Loyola University Chicago. Loyola University, 2011. Web. 13 Nov. 2013.

Merline, John. “ObamaCare Will Now Add To Deficits In First 10 Years.” Investor’s Business Daily. Investor’s Business Daily, 12 July 2013. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Elmendorf, Douglas W. “Letter to John Boehner.” CBO.gov. Congressional Budget Office, 24 July 2012. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.