“Most people on the individual market are getting more benefits under the law. At worst, they’re paying more to get more, though in many cases they’re actually paying less.”

“Most people on the individual market are getting more benefits under the law. At worst, they’re paying more to get more, though in many cases they’re actually paying less.”

—PolitiFact, from a March 20, 2014 fact check of an Americans for Prosperity ad.

Overview

Is “Fact Checkers for Mendacity” the answer to Americans For Prosperity?

The Facts

The political action group Americans for Prosperity ran an anti-Obamacare ad in a number of states. The ad claimed, among other things, that millions of Americans are paying more yet getting less under Obamacare. PolitiFact focused on that claim in a fact check published on March 20, 2014.

PolitiFact ruled it “False” that Americans are paying more yet getting less. Roughly one-third (by area) of the fact check was dedicated to showing that large group health insurance premiums have risen more slowly, on average, during the Obama presidency.

When it came to receiving less under Obamcare, PolitiFact asked for and received from AFP an explanation of what was meant.

Via PolitiFact:

“Getting less speaks to a multitude of data points that has been America’s Obamacare experience so far: botched website, shrinking provider networks, a string of broken promises, missed deadlines, and unilateral rule changes that have kept the entire country in limbo ever since this debacle rolled out,” said spokesman Levi Russell.

PolitiFact judged AFP’s definition ambiguous, said “We think most people would assume “less” is referring to the amount of coverage or benefits under the law,” and proceeded with the fact check using that definition.

Analyzing the Rhetoric

Fact checkers rightly consider the way an audience might perceive a statement, but they err if audience perception completely negates normal charitable interpretation. As a matter of correct procedure, a fact checker must consider every plausible interpretation of a statement.

PolitiFact obviously fails this test. There’s nothing implausible about the AFP ad talking about many different effects of Obamacare as ways Americans get less for their money. At first blush, every point AFP spokesman Russell made looks solid. But to keep our evaluation of PolitiFact’s ruling simple, we’ll stick to aspects of the law relating directly to Americans receiving less in terms of health care.

Paying more

PolitiFact conceded that some people would pay more for insurance in the individual market, and other than that did little to fact check this part of the ad’s claim. We’re not sure why PolitiFact dedicated so much space to documenting a slower rise in health care premiums widely understood as resulting from the weak economy. Especially since the ACA was sold as one of the administration’s key fixes for the weak economy.

PolitiFact waffled between lower health care premiums in the large group market—the market least affected by the ACA—and the ACA’s minimum coverage requirements. PolitiFact admitted the increased level of coverage would come with a cost.

Getting less?

With people paying higher premiums for more expansive insurance coverage, PolitiFact couldn’t see how people would get less:

We found it strange that the ad claimed that people are getting less under the Affordable Care Act. In fact, we’ve usually heard the opposite from critics of the law that people are now paying for types of coverage they don’t need.

We found it strange that a fact checker would fail to distinguish between insurance coverage and health care. If one has more expansive insurance but receives less tangible benefit from that insurance, is the customer receiving more for his dollar? And what of deductibles and co-pays? And Medicare Advantage? PolitiFact’s fact check ignores them.

Insurance differs from health care

There’s a huge difference between the benefits promised by insurance and the benefits literally provided by insurance. Yet PolitiFact effectively ignores the important difference in its fact check.

We can illustrate the difference most obviously where one is insured against a very unlikely event. Imagine an insurance salesman peddling policies to Alaskan Eskimos. The policies would pay for all medical care needed in the event of a crocodile attack. Only $30 per month! And no cap on benefits. What a deal!

Obviously it’s a rip-off, unless the Eskimo is planning a vacation involving skin-diving explorations of Australian rivers or the like. And there’s a direct parallel in the ACA.

The ACA mandates maternity care for all policies in the individual market and most in the small group market. An individual male is no more likely to need maternity coverage than an Alaskan Eskimo is likely to need coverage for crocodile attacks. Yet a single, unattached male will pay for a benefit he’s not at all likely to need. For PolitiFact, getting charged for types of coverage one is unlikely to ever need counts as getting more:

So are you getting less coverage, or getting more than you need?

… it’s a tough sell to say millions are getting less.

Getting coverage one does not need results in paying for health care services one does not receive. In cases like this, more coverage results in the same health care services received and less value in services per insurance dollar. The policyholder pays more to add crocodile insurance and gets less in return.

Shrinking provider networks

Health care consumers will receive less under Obamacare in terms of provider networks. Neither PolitiFact nor Americans for Prosperity mention this, though it figures to represent one of the key means insurance companies use to control costs. In fact, the Obama administration recently reacted to widespread concerns about narrow provider networks in 2014 by again changing the rules:

The Obama administration is requiring health plans in Obamacare insurance marketplaces to include a more robust offering of care providers in 2015 after some early backlash over limited networks in the health care law’s first year.

Health plans selling on the federal marketplaces in 2015 must include 30 percent of area “essential community providers,” which are usually health centers and other hospitals serving mostly low-income patients. That’s up from a 20 percent requirement in 2014, the first year of expanded overage under the health care law.

Consumers will regain some freedom with the new rules, but costs will go up. The ACA gives many consumers fewer provider options. Some of the consumers receiving less are paying more at the same time.

Copays deductibles, and coinsurance

Unbelievably, PolitiFact doesn’t mention copays or deductibles in its fact check. Is the consumer getting less if his deductible goes up? Of course. Is the consumer getting less if co-pays go up? Absolutely. The same goes for coinsurance.

PolitiFact did, however, make sure to mention that the ACA mandates free preventive care. That doesn’t mean consumers aren’t paying for it. It’s paid for through premiums, but without a copay. So PolitiFact tells us the lack of a copay is a benefit but doesn’t seem to acknowledge that a higher copay means consumers receive less.

The ACA causes an increase in deductibles, copays and coinsurance. Insurance companies make those increases largely to counter the cost of the ACA’s caps on out-of-pocket expenses. The cap on out-of-pocket expenses certainly counts as a benefit, but for most consumers it’s like crocodile insurance for Eskimos. In terms of health care benefits, most insurance consumers are getting less. They’re paying the bills for the small number of consumers who spend the out-of-pocket maximum.

Medicare Advantage

PolitiFact also exhibited a blind spot for the ACA’s effects on Medicare Advantage. Kaiser Health News reported earlier this year on insurance industry complaints about the effects of the ACA (bold emphasis added):

The health insurance industry points to these examples as some of the more extreme cases of beneficiaries feeling the sting of federal funding cuts to Medicare Advantage plans that cover nearly 16 million senior citizens. They say the Obama administration’s additional proposed 1.9 percent in cuts to the plans for 2015, which was announced Friday, will mean millions more will see reductions in benefits and higher out-of-pocket costs.

As with so much of the ACA, the Obama administration has delayed the full effects of cuts on Medicare Advantage. The insurance companies may have oversold the impact of the cuts in hopes of obtaining more delays in full implementation of the law. If so, it may have worked:

Medicare has reversed proposed payment cuts to private heath plans in the popular Medicare Advantage program for the second straight year amid strong pushback from health insurers and Capitol Hill.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on Monday, after proposing in February a 1.9 percent cut to private plans, said government payments to insurers in the Medicare Advantage program will increase .4 percent on average in 2015. The increase, CMS said, is slightly higher than what insurers had requested.

Though the administration delayed the bulk of the ACA’s cuts to Medicare Advantage, the ACA unquestionably makes changes to Medicare Advantage that pressure insurance providers to either cut benefits or raise premiums—or both. If the latter happens, those Medicare Advantage policyholders are paying more and getting less.

Millions?

We know that millions are paying more under the ACA. But are millions both paying more and getting less?

A rough estimate helps show that the ad’s claim is quite plausible.

- Shrinking provider networks mostly affect individual and small group insurance, the segments of the market required to offer the ACA’s “essential benefits package.” A study by the McKinsey Company estimated that 70 percent of exchange plans feature either narrow or ultra-narrow provider networks. Based on the administration’s claim of 8.1 million plan sign ups through the exchange, if only 10 percent pay a higher premium and enter a narrower network brought on by the ACA, then about 800,000 are paying more and getting less.

- Higher deductibles under the ACA will affect all types of private insurance, but we’ll draw our estimate from employer-provided insurance. Trends show a rapid increase in the number of firms offering high-deductible plans. About 150 million Americans receive health insurance through their employer. If only 1 percent of Americans with employer-provided insurance pay more for a plan with higher deductibles, then 1.5 million are paying more and getting less.

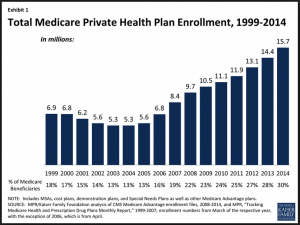

- Medicare Advantage covered 14.4 million seniors in 2013. In 2014, that number jumped to 15.7 million (See chart from the Kaiser Family Foundation, right). If only 0.1 percent of 2013 Medicare Advantage policyholders experienced higher premiums and service cuts as a result of the ACA’s cuts to reimbursement rates, then 14,400 Medicare Advantage beneficiaries are paying more and receiving less. This number is likely to rise sharply if the administration applies the law as it promised.

Our conservative estimate totals 2.3 million persons paying more and getting less thanks to insurance industry changes wrought by Obamacare. Does 2.3 million count as “millions”? We think it’s hard to argue it doesn’t, and we have by no means tried to inflate our estimate. We have mainly worked in the neighborhood of PolitiFact’s narrow definition of “getting less” and not the broad definition sketched by the AFP spokesperson.

We’ll emphasize again one of our main principles of fact-checking: Every person making a claim is entitled to charitable interpretation. That means if AFP plausibly explains its claim then the fact check needs to work from that explanation. The way an audience may interpret a claim is relevant, but it does not negate the relevance of the speaker’s intent. Sometimes majority opinion is wrong, which explains why the appeal to popularity counts as a logical fallacy. PolitiFact erred by judging the intent of the AFP ad based on how most people would interpret the claim in the ad. And it compounded the error by dismissing as too vague the understanding suggested by AFP’s spokesperson.

Summary

We do not claim to have definitively settled whether millions are paying more and getting less with Obamacare. We think our conservative estimate suggests it is likely the ad makes a true claim. And we believe our analysis shows conclusively that PolitiFact did not even start to fact check the claim seriously.

“Most people on the individual market are getting more benefits under the law”

We trust PolitiFact correctly states that most people are getting more comprehensive insurance under the ACA. But PolitiFact omits important context by ignoring the role of copays, deductibles and coinsurance in its estimate of insurance benefits. By judging the increase in benefits according to a narrow set of criteria, PolitiFact makes itself guilty of cherry-picking the data, a form of the Texas sharpshooter fallacy. Also, PolitiFact’s statement does nothing to contradict the claim in the AFP ad that millions will pay more and get less. The individual market accounts for a fraction of insured Americans, and even if most Americans with any kind of private insurance were getting more benefits under the law, it would still leave room for millions of Americans to receive less while paying more. So PolitiFact’s claim is also a red herring fallacy, distracting from the issue PolitiFact claims to fact check.

“At worst, they’re paying more to get more”

![]()

At worst, they’re paying more and getting less. And there are probably millions in that situation with more to come under the ACA. On its key finding against the ad, PolitiFact makes a false claim.

“though in many cases they’re actually paying less.”

![]()

It’s irrelevant to the truth value of the ad’s claim if many are paying less.

References

Contorno, Steve. “Americans for Prosperity Claims People Are Getting Less at a Higher Cost under Obamacare.” PolitiFact. Tampa Bay Times, 20 Mar. 2014. Web. 12 May 2014.

Brown, Carrie Budoff. “Barack Obama Stresses Health Care as an Economic Necessity.” POLITICO. Capitol News Company LLC, 3 June 2009. Web. 12 May 2014.

Dalmia, Shikha. “Obama’s Health Care Reform Tactics.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 5 May 2009. Web. 12 May 2014.

“Age Rating.” AHIP.org. America’s Health Insurance Plans, n.d. Web. 13 May 2014.

Millman, Jason. “White House Orders Broader Obamacare Health Plans in 2015.” Washington Post. The Washington Post, 14 Mar. 2014. Web. 14 May 2014.

United States. Department of Health & Human Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Frequently Asked Questions on Essential Community Providers. Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight, 13 Mar. 2013. Web. 14 May 2014.

Davis, Elizabeth. “Out-of-Pocket Maximum—How It Works and Why to Beware.” About.com. About.com, 8 May 2014. Web. 14 May 2014.

Ornstein, Charles. “Coming in January: Obamacare Rate Shock Part Two.” ProPublica. Pro Publica Inc., 12 Nov. 2013. Web. 14 May 2014.

Galewitz, Phil. “Impact Of Medicare Advantage Cuts On Seniors Sharply Disputed.” KHN: Kaiser Health News. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 23 Feb. 2014. Web. 14 May 2014.

“Medicare Advantage Fact Sheet.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Family Foundation, n.d. Web. 14 May 2014.

Clemans-Cope, Lisa, Bowen Garrett, Katherine Hempstead, and Nathaniel Anderson. “Expectations for Health Care Quality, Access, and Costs in 2014 | Health Reform Monitoring Survey.” Urban.org. The Urban Institute, 4 Feb. 2014. Web. 15 May 2014.

“Report to Congress on the Impact on Premiums for Individuals and Families with Employer – Sponsored Health Insurance from the Guaranteed Issue, Guaranteed Renewal, and Fair Health Insurance Premiums Provisions of the Affordable Care Act.” CMS.gov. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 21 Feb. 2014. Web. 15 May 2014.

Coe, Erica, Chiara Leprai, Jim Oatman, and Jessica Ogden. “Hospital Networks: Configurations on the Exchanges and Their Impact on Premiums.” McKinsey on Healthcare. McKinsey & Company, Dec. 2013. Web. 15 May 2014.

“Release: ESI Declining Amid Rising Costs.” RWJF.org. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 11 Apr. 2013. Web. 15 May 2014.