“The Violence Against Women Act.

“The Violence Against Women Act.

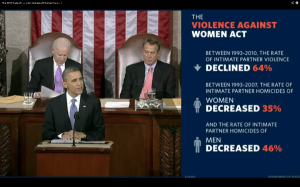

“Between 1993-2010, the rate of intimate partner violence declined 64 percent. Between 1993-2007, the rate of intimate partner homicides of women decreased 35 percent. And the rate of intimate partner homicides of men decreased 46 percent.”

–The White House’s enhanced version of President Obama’s State of the Union speech for 2013

Overview

The White House’s added infographics implicitly and unrealistically credit improved domestic violence statistics to the Violence Against Women Act.

During the State of the Union speech for 2013, President Obama said “We know our economy is stronger when our wives, our mothers, our daughters can live their lives free from discrimination in the workplace, and free from the fear of domestic violence. Today, the Senate passed the Violence Against Women Act that Joe Biden originally wrote almost 20 years ago. And I now urge the House to do the same. Good job, Joe (Vice President Biden).”

The “enhanced” version of the speech produced by the White House showed an infographic during that section of the speech. The infographic followed the bold title “The Violence Against Women Act” with an indented list of stats that changed for the better since the early 1990s.

Analyzing the Rhetoric

We looked into the VAWA in terms of cause-and-effect last week by fact checking a series of stories from PolitiFact. One of the stories had then-candidate Barack Obama crediting his new running mate, Joe Biden, with writing the VAWA. Obama at the same time gave statistics showing decreased domestic violence. PolitiFact said the implied cause-and-effect was questionable but rated the overall claim “Mostly True” since Obama did not directly credit the change to the new law.

The White House’s enhancement of the State of the Union speech renews Mr. Obama’s message implying the VAWA dramatically reduced domestic violence.

Did the VAWA dramatically reduce domestic violence?

In a word, no.

The evidence supporting the effectiveness of the VAWA amounts to very little. One gets the idea of the difficulty from effectiveness reports required of the program:

Measuring the effectiveness of the STOP Program and other VAWA-funded grant programs is a uniquely challenging task.

The 2010 report abundantly illustrates the difficulty by using the services provided as the primary measure of success, supplemented by numerous testimonials from grant recipients detailing the need for the grant money. The report conspicuously refrains from claiming VAWA-funded programs have decreased domestic violence, though the requirement to report efficacy certainly covers that purpose:

In VAWA 2000 Congress broadened existing reporting provisions to require the Attorney General to submit a biennial report to Congress on the effectiveness of activities of VAWA-funded grant programs (Public Law No. 106–386, section 1003 (codified at 42 U.S.C. 3789p)).

The Department of Justice pretty much came up empty with respect to evidence linking the VAWA to lower rates of domestic violence. PolitiFact found its shreds of evidence supporting the effectiveness of the VAWA in a pair of economics studies produced in the early 2000s. A 2003 study by Amy Farmer and Jill Tiefenthaler estimated that 22 percent of the observed reduction in domestic violence came from three factors. The primary factor among the three was the one potentially influenced by VAWA spending: provision of legal services to victims of domestic abuse. But the study also measured the growth of programs supporting victims of domestic abuse and found that such programs saw their greatest growth in numbers in the years preceding the passage of the VAWA.

It seems the VAWA was not the primary driver of the effect estimated by Farmer and Tiefenthaler.

The other study (Clark, Andersen, Biddle, 2002) is easier to dismiss. Economists estimated the cost benefit of the VAWA by assuming it was responsible for between 10 and 100 percent of the reduction in domestic violence. The wide range renders the assumptions untenable, and the authors do not clearly, if at all, explain the justification for a floor as high as 10 percent.

Other evidence of the effectiveness of the VAWA?

In 2004 Kristen J. Roe, the public policy consultant for the National Alliance to End Sexual Violence, published a summary of the law’s effects and noted the lack of evidence that domestic violence had decreased as a result of the law (bold emphasis added):

As the original authorization period for the VAWA came to a close, indications that attitudinal and behavioral changes were occurring across the nation emerged. And, while little to no empirical evidence measuring the effectiveness of VAWA I is available, anecdotal evidence suggests that the original VAWA was a successful start. As a September 1999 report issued by Senator Biden stated, “…we have successfully begun to change attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors related to violence against women.”

Another peer-reviewed study, “How has the Violence Against Women Act affected the response of the criminal justice system to domestic violence?” by Hyunkag Cho and Dina J. Wilke, failed to find any decrease in domestic violence as a result of the law (bold emphasis added):

Why did enactment of the VAWA, the most comprehensive federal legislation addressing domestic violence, not appear to impact the existing trends of domestic violence? First, one might expect the impact of the VAWA enactment to have occurred in later years (i.e., at longer lags) rather than immediately after the fourth quarter of 1994. It is normal that it takes time from the law enactment to its enforcement and implementation. To examine this possibility, additional time series analyses were conducted beginning with the second quarter of 1995 (six months after the VAWA enactment) and the fourth quarter of 1995 (one year after the enactment). There were still no significant changes in the existing trends using this strategy. Therefore this explanation appears not to be plausible …

A second possible explanation is contrary to the first; if the expected changes for the interested variables were already occurring before enactment of the VAWA, the impact of the VAWA would have been minimized. … these trends could not be examined in this study due to the lack of data before the 1990s.

The second explanation the study offers doesn’t do anything to support the VAWA as an effective measure reducing domestic violence.

The VAWA has very little support overall as a factor decreasing domestic violence. Any effect the law had on domestic violence was very likely small.

The White House spin

While the president avoided making any claims about the VAWA accounting for a decrease in domestic violence, the version the White House enhanced with infographics emphasized the role of the VAWA in lowering domestic violence. The title of the video sidebar spells out “The Violence Against Women Act” in bold block letters against a deep blue background. Below that heading, with an indented structure we associate with an outline, the sidebar lists sensational decreases in domestic violence.

The infographic is clearly intended to credit the VAWA with a lion’s share of the decreases if not the whole. Absent that association, no good reason exists for showing the statistics.

Summary

“The Violence Against Women Act.

“Between 1993-2010, the rate of intimate partner violence declined 64 percent. Between 1993-2007, the rate of intimate partner homicides of women decreased 35 percent. And the rate of intimate partner homicides of men decreased 46 percent.”

We think it likely the administration knows better than to credit all or even most of the decreasing domestic violence trend to the Violence Against Women Act.

References

Phillips, Macon. “You’ve Never Seen a State of the Union Address Like This Before.” The White House Blog. The White House, 24 Jan. 2011. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

Obama, Barack. “State of the Union 2013.” The White House President Barack Obama. The White House, Jan. 2013. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

Rubin, Richard. “Cause and Effect? Possible, but Not Clear.” PolitiFact. Tampa Bay Times, 24 Aug. 2008. Web. 25 Feb. 2013.

“USDOJ: Office on Violence Against Women: Reports to Congress.” USDOJ: Office on Violence Against Women: Reports to Congress. U.S. Department of Justice, n.d. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

White, Bryan W. “PolitiFact Claims the Violence Against Women Act Accounts for a Significant Portion of the Decline in Domestic Violence from 1994-2010.” Zebra Fact Check. Zebra Fact Check, 20 Feb. 2013. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

“The Violence Against Women Act and Its Impact on Sexual Violence Public Policy: Looking Back and Looking Forward.” Publications | National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC). National Sexual Violence Resource Center, n.d. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

Roe, Kristen J. “The Violence Against Women Act and Its Impact on Sexual Violence Public Policy: Looking Back and Looking Forward.” National Sexual Violence Resource Center. National Sexual Violence Resource Center, 2004. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

Muhlhausen, David. ““Violence Against Women Act” Gives Grant Money to Misleading Organizations.” The Foundry Conservative Policy News Blog. The Heritage Foundation, 13 Feb. 2013. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

Cho, Hyunkag, and Dina J. Wilke. “How has the Violence Against Women Act affected the response of the criminal justice system to domestic violence.” J. Soc. & Soc. Welfare 32 (2005): 125. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

Video