“Kaine said Castile was stopped by police 40 or 50 times before the time when he was fatally wounded. According to multiple independent press reports, that is accurate. Police had stopped Castile at least 46 times.”

“Kaine said Castile was stopped by police 40 or 50 times before the time when he was fatally wounded. According to multiple independent press reports, that is accurate. Police had stopped Castile at least 46 times.”

—PolitiFact, from a fact check of Democratic vice-presidential candidate Tim Kaine, Oct. 5, 2016

Overview

PolitiFact largely drops the context of Kaine’s remark, failing to consider whether Philando Castile’s record of traffic stops properly supported Kaine’s point.

Background Facts

On Oct. 4, 2016, Democrat Tim Kaine and Republican Mike Pence engaged in a vice-presidential debate. The topic of racism in police procedures came up, and Kaine used the example of Philando Castile to buttress the notion that police use race as a criterion for making traffic stops (bold emphasis added):

KAINE: Elaine — Elaine, people shouldn’t be afraid to bring up issues of bias in law enforcement. And if you’re afraid to have…

PENCE: I’m not afraid to bring that up.

KAINE: And if — if you’re afraid to have the discussion, you’ll never solve it. And so here’s — here’s an example, heartbreaking. We would agree this was a heartbreaking example.

The guy, Philando Castile, who was killed in St. Paul, he was a worker, a valued worker in a local school. And he was killed for no apparent reason in an incident that will be discussed and will be investigated.

But when folks went and explored this situation, what they found is that Philando Castile, who was a — they called him Mr. Rogers with Dreadlocks in the school that he worked. The kids loved him. But he had been stopped by police 40 or 50 times before that fatal incident. And if you look at sentencing in this country, African-Americans and Latinos get sentenced for the same crimes at very different rates.

Kaine implied that the number of times Castile was stopped serves as an example of bias. PolitiFact fact-checked Kaine’s claim about the number of traffic stops and acknowledged that was Kaine’s underlying point:

We know the larger point Kaine was making and we’ve checked that before (True). But we wanted to vet his number for how many times police stopped Castille.

To establish the legitimacy of Kaine’s underlying point, PolitiFact linked to its own fact check looking at whether blacks are charged with more crimes than whites and receive harsher sentences for the same crimes than whites.

Our fact check will look at whether the police stops of Castile rightly contribute to the idea police use race as a criterion for stopping motorists. We will also touch on the evidence PolitiFact used to imply that Kaine’s larger point was true.

Analyzing the Rhetoric

Given that Kaine was making the point that police employ bias when stopping motorists, his example involving Philando Castile needs to provide reasonable evidence that at least some of the stops Castile endured were motivated by racial bias. The number of stops counts as a secondary consideration. If Castile was stopped 1,000 times for reasons apart from bias it would not help Kaine’s point.

We found that PolitiFact’s ruling focused narrowly on whether Kaine was right about the number of times police stopped Castile. And to support Kaine’s point about bias, PolitiFact cited a story by National Public Radio and one of its own fact checks.

PolitiFact cited a story from National Public Radio to show the police stops of Castile reflected racial bias:

A similar investigation by NPR found 46 stops. And NPR noted “Of all of the stops, only six of them were things a police officer would notice from outside a car — things like speeding or having a broken muffler.”

If NPR correctly concluded that only six of the traffic stops were justified by appearances, it would count as a reasonable evidence that Castile was somehow targeted based on his race.

NPR’s View of Castile’s Traffic Stops

NPR’s View of Castile’s Traffic Stops

Our review of NPR’s research left us with gigantic doubts about its conclusion.

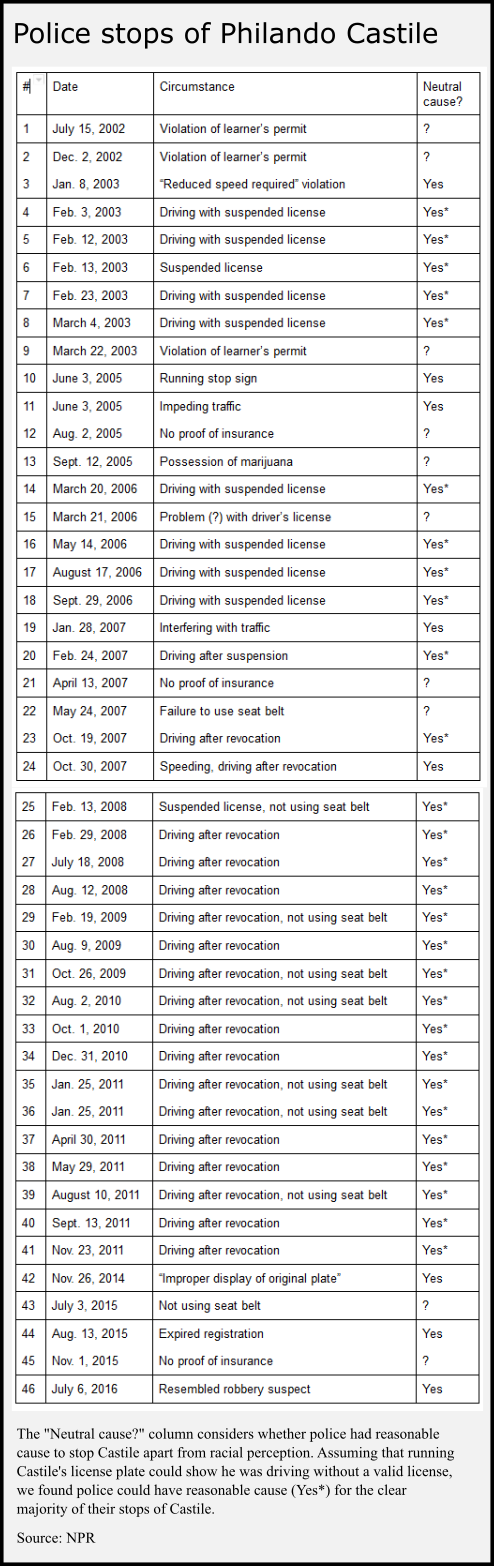

NPR counted 46 traffic stops of Castile, along with four parking tickets. We accept that as solid evidence that Castile was stopped by police around 40 or 50 times, as Kaine said.

We condensed the information collected by NPR into a table embedded to the right, showing all 46 traffic stops NPR counted along with the circumstance and a judgment on whether police could have discovered the listed circumstance without first stopping Castile.

Was NPR right that only six of Castile’s stops were for things a police officer would notice from outside a car?

We counted 28 times Castile was cited for driving despite a suspended or revoked license. Police routinely enter the license plate numbers they observe into their on-board computers. Though police departments use many different types of software in their computers, among the most common data retrievals involves the status of the driver’s license of a vehicle owner.

Police also cited Castile a number of times for not wearing his seat belt. Police may observe a driver’s failure to wear a seat belt. Some police departments encourage officers to use night vision goggles to allow them see this infraction at night. Police may see a motorist failing to use a seat belt before pulling the car over.

NPR’s reporting does far too little to assure readers that its conclusion holds water. To unequivocally state that only six of Castile’s stops were justified by observation, NPR should rule out the possibility that running Castile’s license plate or observing the position of the shoulder strap of his seat belt led to his traffic stops.

Indeed, NPR’s research provides no assurance that any police stop of Castile was not justified by prior observation.

This aspect of NPR’s story encourages the impression that NPR was inventing the news instead of reporting it.

Trust NPR?

PolitiFact’s choice of NPR as a source had its positive side: NPR gave readers the information on which it based its reporting, in the form of condensed police reports. That allows the reader to verify that NPR’s reporting makes good sense of the data.

In this case, unfortunately, NPR’s conclusion relied on the assumption that police cannot have good reason for thinking the operator of a vehicle has no valid license before making a traffic stop.

PolitiFact should have noted signs of problems with NPR’s reporting.

The Larger Point Settled?

PolitiFact gave its readers the impression that Kaine’s larger point, that police show bias against blacks, is simply true. In making that claim, PolitiFact linked to its Feb. 26, 2016 fact check of a statement from Hillary Clinton. Clinton said blacks are more likely to be arrested than whites and receive longer sentences for the same offenses. PolitiFact said that was “True” while noting that it was not clear to what degree racism accounting for the disparity:

How much of this is due to racism is a matter of debate. The experts say poverty may play a major role, but it can be hard to separate the two. The best studies try to adjust for the fact that minorities tend to be concentrated in poorer areas, where crime tends to be higher and there’s a greater demand for police. That can skew the numbers.

How then would the Clinton fact check settle Kaine’s point about police bias?

Unaccountably, PolitiFact overlooked its own conflation of correlation with causation. If police proportionally arrest blacks more often than whites, it follows that bias serves as the cause only if blacks do not commit proportionally more crimes than whites. PolitiFact’s reporting ignored the latter question.

PolitiFact offered correlation as proof police bias was the cause, resulting in a false cause fallacy.

Conclusion

The data PolitiFact provided do not tell us whether blacks are arrested more often and receive harsher sentences because of bias. Nor did PolitiFact provide data showing that the 46 traffic stops of Philando Castile were motivated by any type of bias. Yet PolitiFact gave Democrat Tim Kaine credit for a true underlying argument about police bias.

“Police had stopped Castile at least 46 times.”

While it is true, as Kaine said, that Castile was pulled over 40 or 50 times before he was shot by police, the statistic carries no logical weight in the context Kaine used it. PolitiFact’s approval of Kaine’s claim reflects a false cause fallacy, inferring racial bias despite a lack of reasonable evidence. We also judge that PolitiFact omitted important context. When PolitiFact cited its own work in supporting Kaine’s argument about bias, it failed to heed the statement in that fact check declaring that evidence of racial bias was unclear.

Reference Materials

“PolitiFact’s Annotated Transcript of the Vice Presidential Debate.” Medium. PolitiFact, 04 Oct. 2016. Web. 07 Oct. 2016.

Greenberg, Jon. “Kaine: Police Stopped Slain Minnesota Driver over 40 times.” PolitiFact. Tampa Bay Times, 05 Oct. 2016. Web. 07 Oct. 2016.

Emery, C. Eugene, Jr. “Hillary Clinton Says Blacks More Likely to Be Arrested, Get Longer Sentences.” PolitiFact. Tampa Bay Times, 26 Feb. 2016. Web. 07 Oct. 2016.

Corley, Cheryl. “The Driving Life And Death Of Philando Castile.” NPR. NPR, 15 July 2016. Web. 07 Oct. 2016.

Higgins, Michael. “Suit Alleges Racial Profiling Via Cops’ Computer Checks.” Chicago Tribune. Chicago Tribune, 08 June 2000. Web. 07 Oct. 2016.

“Operating With a Suspended License Motor Vehicle Infractions.” Spring & Spring. Spring & Spring, n.d. Web. 07 Oct. 2016.

“License Plate Checks.” Law Officer. Law Officer, 01 July 2008. Web. 07 Oct. 2016.

“MN State Patrol License Plate Reader (LPR) Fact Sheet.” Minnesota Senate. Minnesota Senate, Feb. 2015. Web. 07 Oct. 2016.