Los Angeles Times columnist Michael Hiltzik blasted PolitiFact Oregon, among other PolitiFacts, with a Sept. 10, 2014 column titled “Another ‘fact-checker’ gets Social Security wrong.”

We have complaints about the PolitiFact Oregon item, also. But Hiltzik’s demagogy takes precedence. This paragraph encapsulates Hiltzik’s most objectionable points:

The money accounted for in the trust fund was borrowed by the federal government and spent on non-Social Security needs, as PolitiFact’s own source says. When the bonds are redeemed, that’s a repayment transaction exactly equivalent to what happens when you repay your mortgage, not a deficit-creating transaction. Even if you want to say that paying interest or principal on the bonds adds to the deficit, it’s the spending on those non-Social Security needs that created the deficit, not Social Security.

Lest Hiltzik get away with playing a shell-game here, PolitiFact Oregon found it was at least partly true that Social Security contributes to the federal deficit when the former brings in less revenue than it spends on benefits. Hiltzik is right that the federal government borrowed the money, but what choice did the federal government have when Social Security was buying bonds with its excess? Let’s be real: Part of the point of Social Security is to loan that excess to the federal government. Social Security is not the victim of the government borrowing. Loaning the government the money is an integral part of Social Security’s pay-as-you-go structure.

Hiltzik goes on to make his key claim, “When the bonds are redeemed, that’s a repayment transaction exactly equivalent to what happens when you repay your mortgage, not a deficit-creating transaction.” No, it’s not exactly equivalent to repaying your mortgage, unless you loaned yourself the money and are repaying yourself. Remember, we’re talking about Social Security’s effect on the federal deficit.

A deficit represents an annual balance sheet. If the federal government pays down debt, as by redeeming bonds purchased with excess payroll taxes, that’s an expense that contributes to a budget deficit. Therefore, contrary to Hiltzik’s claim, it is a deficit-creating transaction.

Hiltzik makes a lame attempt to justify his reasoning, saying “Even if you want to say that paying interest or principal on the bonds adds to the deficit, it’s the spending on those non-Social Security needs that created the deficit, not Social Security.” Do we need to remind Hiltzik that the spending that created the “deficit” was, at least in part, from prior fiscal years? That earlier spending of bond money contributes to the former debt, not the present deficit. And even if it hadn’t been spent, repaying the loan with interest contributes to the deficit for any given year. If I borrow $50 in fiscal year 2008 and save that money in a desk drawer only to repay it in FY2009, it counts as $50 of spending in 2009. Hiltzik’s attempt to shift the blame is beyond silly.

Hiltzik caps his confusion of the debt with the deficit with this:

If it doesn’t bring in enough money to pay benefits, those benefits will have to be cut, by law. It can’t spend more than it takes in, so it can’t add to the federal deficit. Period.

Hiltzik’s reasoning just doesn’t follow. Federal spending, and any annual deficit, grows when the federal government redeems bonds used to pay Social Security benefits. Period.

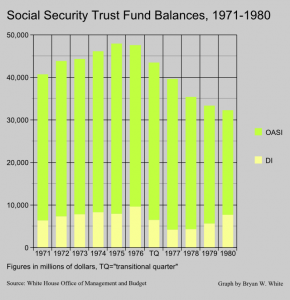

Hiltzik’s reasoning might follow if we considered Social Security as a totally separate entity and considered only whether Social Security itself was running a deficit. But we’re considering the question of the federal deficit. And, as we pointed out in an email to PolitiFact Oregon, Social Security ran deficits in the 1970s during a time when the program was on-budget. Trust fund balances dropped, which is what happens when a program runs a deficit for a given year.

Hiltzik’s reasoning might follow if we considered Social Security as a totally separate entity and considered only whether Social Security itself was running a deficit. But we’re considering the question of the federal deficit. And, as we pointed out in an email to PolitiFact Oregon, Social Security ran deficits in the 1970s during a time when the program was on-budget. Trust fund balances dropped, which is what happens when a program runs a deficit for a given year.

Social Security contributes to the federal deficit beyond what PolitiFact admits and way beyond the claims in Hiltzik’s Escheresque column.

That’s the fact of the matter.

Update Sept. 13, 2014

Hiltzik reiterates his false claim Social Security has never contributed to the federal deficit with a Sept. 12 column titled “A ‘fact-checking’ website doubles down on its Social Security errors.”

Not all of Hiltzik’s criticisms of PolitiFact Oregon miss their mark. For example, Hiltzik is correct to point out that his first name is “Michael” and not “Thomas.” Hiltzik’s central claim, however, remains as false as it was in his Sept. 10 column.

We tried to help Hiltzik see the error of his ways via Twitter. Where Hiltzik mocked the idea of Social Security contributing to the deficit by pointing to the absurdity of statements like “China contributes to the deficit” or “little Johnny who got savings bonds for his birthday contributes to the deficit,” we suggested the alternative “Paying interest on the national debt (such as T-bills) increases the deficit.”

Richard L. Kaplan makes the point even more powerfully in his 1995 journal article Top Ten Myths of Social Security:

Although Social Security as a distinct problem is in “surplus,” that situation will change within a few decades. More importantly, the constitution of Social Security beneficiary payments is a government expenditure like any other expenditure, and failing to reduce or change those payments impacts federal outlays and the resulting deficit.

Kaplan points out that nothing stops the government, in principle, from lowering or stopping Social Security benefits entirely while keeping the funds invested in treasury bills for its own use. That move would dramatically lower the deficit, illustrating in overpowering terms the reality of Social Security’s impact on the deficit. Social Security researcher Sally R. Sherman made a parallel observation back in 1989.

Hiltzik has no leg to stand on.