“After five years of retirement, when you’re 70 years old, you could lose $645. And after 10 more years, when you’re 80 years old, you would’ve lost a grand total of $5,113. In 25 years under chained CPI, you would’ve lost a grand total of $13,715. That’s almost $14,000 of your hard-earned money, snatched from your wallet.”

“After five years of retirement, when you’re 70 years old, you could lose $645. And after 10 more years, when you’re 80 years old, you would’ve lost a grand total of $5,113. In 25 years under chained CPI, you would’ve lost a grand total of $13,715. That’s almost $14,000 of your hard-earned money, snatched from your wallet.”

–David Certner, AARP director of legislative policy

Overview

AARP’s incredibly one-sided explanation combines ballpark accuracy with misleading omissions.

The Facts

In 2002, the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics responded to criticisms of the standard method of calculating cost-of-living increases by publishing statistics for a new method of calculation, known as the chained CPI. The introductory report said “The new measure is designed to be a closer approximation to a “cost-of- living” index than the existing BLS measures.”

CPI stands for consumer price index. The CPI keeps track of inflation by assessing the costs of a set of representative items as they change over time. The BLS has more than one CPI measure.

CPI-U: The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers.

CPI-W: The Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers. This is the index now used to calculate cost of living adjustments for Social Security beneficiaries.

C-CPI-U: The chained CPI modifies the old measurements by accounting for changes in consumer behavior in response to changing prices. If the cost of beef rises sharply, for example, consumers respond by purchasing alternatives such as chicken.

The bipartisan Moment of Truth Project calls the chained CPI a more accurate measure of inflation than the traditional measure. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget defends chained CPI from charges that it has regressive effects on income. The Center for Economic and Policy Research charges that the chained CPI shortchanges retired persons by failing to account for an added impact from housing and medical costs in the elderly population.

The AARP spokesperson, Certner, makes a case against applying the chained CPI to Social Security beneficiaries in a “white board” video presentation (transcript ours, bold emphasis added):

Basically, anyone receiving Social Security or veteran’s benefits would be hurt by chained CPI. We’re talking about retirees, widows, children, people with disabilities and retired and disabled veterans.

It affects people now, and well into the future. So whether you receive benefits now or ten years from now, you will feel the pain of this cut.

Let’s take a look at what I mean.

So for the average retiree, if chained CPI passes, your benefit is cut by $43. By the second year, it’s $43 plus another $43. And then by the third year, it’s 43 plus 43 plus another $43.

So you start to see why this is a problem. The cut starts out small, but grows larger and larger over time. The older you get, the more you rely on Social Security as your other savings begin to run out, the bigger the cut. So let’s say you’re the average retiree. You’re 65 years old. The chained CPI would end up reducing your income by thousands of dollars. Let’s take a closer look at how much you could lose over your lifetime.

After five years of retirement, when you’re 70 years old, you could lose $645. And after 10 more years, when you’re 80 years old, you would’ve lost a grand total of $5,113. In 25 years under chained CPI, you would’ve lost a grand total of $13,715. That’s almost $14,000 of your hard-earned money, snatched from your wallet.

Think about it. That means it’s going to be harder and harder to pay for basic things, like food and prescription drugs and utilities. This is simply bad policy. And it’s unfair to seniors who count on this money. So the next time you hear the phrase “chained CPI,” you should visualize your hard-earned Social Security benefits on the chopping block.

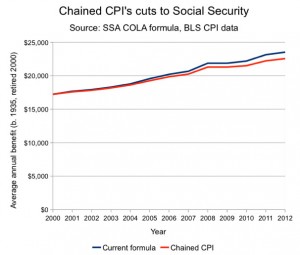

Analyzing the Rhetoric

At least one aspect of Certner’s presentation rings true: Using chained CPI as a replacement for the traditional measure will cost Social Security beneficiaries. The chained CPI will tend to give a smaller cost of living adjustment than the unchained CPI. Certner spins the changes somewhat by calling them decreases in benefits. Relative to the present calculation of cost-of-living adjustments, the changes represent a decrease in benefits. Relative to each preceding year, assuming an increase in the cost of living, the Social Security recipient under chained CPI will receive a greater benefit, though not as great an increase as projected under the current system.

Certner’s failure to mention that chained CPI results in positive cost-of-living adjustments encourages his audience to fall victim to a fallacy of ambiguity. His rhetoric sets a booby trap for less-informed viewers who may conclude that chained CPI literally reduces the total Social Security benefit from one year to the next. This theme repeats itself a number of times in different ways during Certner’s presentation.

“You will feel the pain of this cut”

Chained CPI will nearly always represent a cut in the rate of increase in benefits. It will not result in a cut in benefits year to year where the cost of living increases.

“The chained CPI would end up reducing your income by thousands of dollars.”

The chained CPI, over time, could reduce a Social Security recipient’s income over time by thousands of dollars relative to the benefit increase expected under the current system. Income would not decrease by thousands of dollars relative to the Social Security benefit received during a beneficiary’s first year.

“In 25 years under chained CPI, you would’ve lost a grand total of $13,715. That’s almost $14,000 of your hard-earned money, snatched from your wallet.”

Is a Social Security benefit “your hard-earned money”?

This word choice by Certner helps reinforce a common misconception about Social Security. Social Security is not a savings program. A beneficiary does not draw out his contributions with interest upon retirement. New retirees receive their benefits primarily from the payroll deductions of today’s workers. The center-left Urban Institute sums up the situation succinctly:

Is the trust fund a fiction? Was the trust fund raided? You know, it scarcely matters. All these debates are over a tiny sliver of the Social Security System—not over where the real action is.

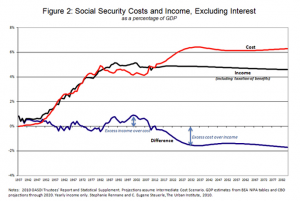

What does matter is that Social Security expenses are expected to rise by about 50 percent—from about 4.3 to 6.3 percentage points of GDP—from 2008 to 2030, and taxes aren’t.

The Social Security trust fund at best pays a small part of Social Security benefits. Most of the payroll taxes go directly to Social Security recipients.

The Social Security program continues to present itself as an insurance program. The government rests under no obligation to meet a particular schedule of benefits. It can cut benefits if it chooses. So the benefits are “hard-earned” only in the sense that one has paid a premium for retirement insurance. The government gets to choose the benefit, thus using chained CPI to calculate COLAs does not deprive recipients of their earned benefits. It means that the government has decided that beneficiaries earned less in benefits through their premium payments.

“So the next time you hear the phrase “chained CPI,” you should visualize your hard-earned Social Security benefits on the chopping block.”

Certner’s rhetoric, in addition to encouraging a false notion of cash flow in the Social Security system, suggests an oversimplified picture of future outcomes. Allow COLA adjustments by chained CPI, he appears to say, and one can expect less in benefits than if chained CPI is rejected. That picture of the future neglects the basic fiscal problem for Social Security that the Urban Institute helped highlight above.

Failing to resolve Social Security’s hemorrhaging finances puts the entire system at risk. The economy probably cannot endure paying the current schedule of benefits indefinitely into the future without reducing the expansion of benefits. Rather than a choice between the current system and a decelerated increase in benefits under chained CPI, Social Security beneficiaries may face a termination of benefits when the government runs out of money to pay the bills. It’s not a simple choice between the old COLA system and chained CPI since the old system may prove unsustainable. The risk to the system at its current growth rate accounts for the bipartisan support chained CPI enjoys.

Summary

“You will feel the pain of this cut”

“The chained CPI would end up reducing your income by thousands of dollars.”

“Your hard-earned money, snatched from your wallet.”

We can imagine accepting this one as true with maximal charitable interpretation, taking the statement as hyperbole. We don’t quite buy it, particularly given the widespread misunderstandings about the funding system for Social Security.

“So the next time you hear the phrase “chained CPI,” you should visualize your hard-earned Social Security benefits on the chopping block.”

Perhaps one should see chained CPI as the choice a candidate for amputation has between losing a leg and dying outright. We don’t know, by analogy, precisely when or if this patient would die, but it’s clear enough that delaying treatment heightens the risk.

Is chained CPI a good COLA measure for retirees?

We wanted to make one more point, addressing the claim that the spending patterns of seniors make chained CPI a poor method for cost-of-living adjustments.

The argument from the Center for Policy and Economic Research relied on an experimental CPI metric, CPI-E, intended to help measure the effects of inflation for the elderly.

The BLS included the following in the conclusion of a paper detailing the method (bold emphasis added):

Finally, the medical care component of the CPI has a substantially larger relative weight in the experimental population compared to the CPI-U or CPI-W. As a result, the medical care component of the CPI-E tends to have a larger effect on the elderly population than it does on the other two populations. However, the experimental price index has limitations as an estimate of the inflation rate experienced by older Americans. Because of the various limitations inherent in the methodology, any conclusions drawn from the data should be interpreted with caution.

We expect the best think-tanks to generally avoid omitting this type of information in their assessments.

We did not encounter solid evidence that chained CPI accounts poorly for changes in the cost of living for the elderly and retired.

Correction and update, April 6, 2013

Corrected a sentence that originally read “The BLS apparently abandoned experimentation with CPI-E in the 1990s, and included the following in the conclusion of a paper detailing the method (bold emphasis added):” The BLS does continue to track the CPI-E, but has yet to withdraw the cautionary language associated with the measure as of Aug. 2012:

To capture the inflation experience of the elderly and make the CPI-E more accurate, new surveys and procedures would have to be created.

Also removed the following statement from our fact check: “Whether it does or not, the BLS no longer tracks CPI-E.”

References

What You Need to Know About the Chained CPI. Perf. David Certner. AARP.org. AARP, Mar. 2013. Web. 23 Mar. 2013.

“Frequently Asked Questions about the Chained Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (C-CPI-U).” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. Department of Labor, 2005. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

U.S.A. United States Department of Labor. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Introducing the Chained Consumer Price Index. By Robert Gage, John Greenlees, and Patrick Jackman. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Introducing the Chained Consumer Price Index. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2003. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Mohr, Angie. “What Is “Chained CPI?”” Yahoo! Finance. Yahoo! – ABC News Network, 31 Jan. 2013. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Greenstein, Robert. “What’s A ‘Chained’ CPI?” Interview by Michele Norris. All Things Considered. PBS. 20 July 2011. Radio. Transcript.

“One Page Summary of “Measuring Up: The Case for the Chained CPI”” Moment of Truth. Moment of Truth Project, 19 Mar. 2013. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

“Once Again, the Chained CPI Is Not Regressive.” Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, 18 Dec. 2012. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Barber, Alan, and Nicole Woo. “The Chained CPI: A Painful Cut in Social Security Benefits and a Stealth Tax Hike | Reports.” CEPR. The Center for Economic Policy Research, Dec. 2012. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Barber, Alan, and Nicole Woo. “The Chained CPI: A Painful Cut in Social Security Benefits and a Stealth Tax Hike.” CEPR. The Center for Economic Policy Research, Dec. 2012. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Matthews, Dylan. “Everything You Need to Know about Chained CPI in One Post.” Washington Post Wonkblog. The Washington Post Company, 11 Dec. 2012. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Steuerle, C. Eugene. “The Pointless Debate Over the Social Security Trust Fund.” Urban Institute. Urban Institute, 24 Mar. 2011. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Tanner, Michael D. “Social Security’s Sham Guarantee.” Cato Institute. Cato Institute, 29 May 2005. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Rivlin, Alice M. “Growing the Economy and Stabilizing the Debt.” The Brookings Institution. The Brookings Institution, 14 Mar. 2013. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Blahous, Charles. “Reforming CPI: Not a “Grand Bargain” but a Prudent Reform.” E21. Economic Policies for the 21st Century, 12 July 2011. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Viard, Alan D. “The Chained CPI: A Path to Bipartisan Deficit Reduction.” American Enterprise Institute. American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 26 Sept. 2011. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

“Press Office: Board of Trustees: Projected Trust Fund Exhaustion Three Years Sooner Than Last Year.” Social Security. U.S. Social Security Administration, 23 Apr. 2013. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Baker, Dean. “Why Are Proponents of the Chained CPI So Scared of Data?” CEPR-blog. The Center for Economic Policy Research, 15 Feb. 2013. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Stewart, Kenneth J., and Joseph Pavalone. “Attachment F: Experimental CPI for Americans 62 Years of Age and Older.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. Department of Labor, Dec. 1996. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Additional works consulted

“Chained CPI Resource Page.” Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, n.d. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Tooley, Mark. “A Liberal Evangelical Resigns From AARP.” The American Spectator. The American Spectator, 22 Feb. 2013. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Gokhale, Jagadeesh. “AARP Misleads Elderly About Social Security’s Fiscal Health.” Investors.com. Investor’s Business Daily, 25 Feb. 2013. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Carroll, Vincent. “AARP’s Scorched-earth Antics.” Denverpost.com. The Denver Post, 17 Mar. 2013. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Sanders, Bernie. “Chained CPI: An Economic, Moral Disaster.” The Hill. Capitol Hill Publishing Corp., 11 Feb. 2013. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.

Jackson, Brooks. “Chained Explained.” FactCheck.org. The Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, 11 Dec. 2012. Web. 24 Mar. 2013.