While fact checking claims PolitiFact Texas made in its fact check of Rep. Louie Gohmert (R-Texas) I ran into the problem of experts giving contradictory opinions.

While fact checking claims PolitiFact Texas made in its fact check of Rep. Louie Gohmert (R-Texas) I ran into the problem of experts giving contradictory opinions.

Gohmert answered a journalist’s question about the justification for citizens having arms similar to those used by law enforcement. Gohmert said his reason was the same as the one that George Washington had for saying a free people ought to be armed. That is, to protect against government tyranny. Experts disagreed on whether Gohmert’s reference to Washington was accurate.

That experts might offer contradictory opinions comes as no surprise. The problem comes in figuring out what to do about it. I roundly criticized PolitiFact for arbitrarily ignoring the opinion of an expert in fact checking Mitt Romney’s claims about President Obama’s “apology tour.” If a fact checker goes against what an expert says then the readers deserve an explanation.

In the fact check article we briefly explained why Gohmert was reasonable to invoke the words of George Washington as he did. Here, we’ll go into greater detail.

“A free people ought not only to be armed, but disciplined”

The statement comes from Washington’s first annual address:

Among the many interesting objects, which will engage your attention, that of providing for the common defence will merit particular regard. To be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace.

A free people ought not only to be armed, but disciplined; to which end a Uniform and well digested plan is requisite: And their safety and interest require that they should promote such manufactories, as tend to render them independent others, for essential, particularly for military supplies.

The proper establishment of the Troops which may be deemed indispensible, will be entitled to mature consideration. In the arrangements which may be made respecting it, it will be of importance to conciliate the comfortable support of the Officers and Soldiers with a due regard to oeconomy.

Context, Context, Context

It’s proper to consider the immediate context of Washington’s speech. Each of the experts agreeing with PolitiFact emphasized that in the immediate context Washington was advocating militia activity under federal government authority. PolitiFact Texas followed that approach to the fact check, emphasizing the immediate context and finding Rep. Gohmert’s claim “False.”

Unfortunately, the focus on the immediate context shortchanged the broader historical context. That broader context comes through abundantly in the documents of the time and in today’s body of professional literature on the Second Amendment.

The framers and the broad context

As noted in our related fact check, key federalists Alexander Hamilton and James Madison used arguments in The Federalist acknowledging the armed population as a check on the risks posed by constitutionally allowing a standing army. The federalists, of course, were the group advocating a strong federal government. The anti-federalists needed convincing because of concerns the federal government would grow its power and engage in tyranny.

Anti-federalist Thomas Jefferson expressed that concern in an 1789 letter to Colonel David Humphreys (bold emphasis added):

The operations which have taken place in America lately, fill me with pleasure. In the first place, they realize the confidence I had, that whenever our affairs go obviously wrong the good sense of the people will interpose, and set them to rights. The example of changing a constitution, by assembling the wise men of the State, instead of assembling armies, will be worth as much to the world as the former examples we had given them. The Constitution, too, which was the result of our deliberations, is unquestionably the wisest ever yet presented to men, and some of the accommodations of interest which it has adopted, are greatly pleasing to me, who have before had occasions of seeing how difficult those interests were to accommodate. A general concurrence of opinion seems to authorize us to say, it has some defects. I am one of those who think it a defect, that the important rights, not placed in security by the frame of the Constitution itself, were not explicitly secured by a supplementary declaration. There are rights which it is useless to surrender to the government, and which governments have yet always been found to invade. These are the rights of thinking, and publishing our thoughts by speaking or writing; the right of free commerce; the right of personal freedom. There are instruments for administering the government, so peculiarly trust-worthy, that we should never leave the legislature at liberty to change them. The new Constitution has secured these in the executive and legislative department, but not in the judiciary. It should have established trials by the people themselves, that is to say, by jury. There are instruments so dangerous to the rights of the nation, and which place them so totally at the mercy of their governors, that those governors, whether legislative or executive, should be restrained from keeping such instruments on foot, but in well-defined cases. Such an instrument is a standing army. We are now allowed to say, such a declaration of rights, as a supplement to the Constitution where that is silent, is wanting, to secure us in these points.

In 1775, Samuel Adams wrote to Elbridge Gerry (bold emphasis added):

It is a misfortune to a Colony to become the seat of war. It is always dangerous to the liberties of the people to have an army stationed among them, over which they have no control. There is at present a necessity for it; the Continental Army is kept up within our Colony, most evidently, for our immediate security. But it should be remembered that history affords abundant instances of established armies making themselves the masters of those Countries which they were designed to protect. There may be no danger of this at present, but it should be a caution not to trust the whole military strength of a Colony in the hands of commanders independent of its established Legislative.

Concern about the usurpation of power in the new government ran high. The framers used the separation of powers within the federal government as a hedge against tyranny. The framers limited the power of the federal government as a hedge against tyranny. And the framers passed the Second Amendment as a hedge against tyranny, especially against the risks posed by a standing army. They had ample reason for fearing a standing army based on their familiarity with recent English history, including Oliver Cromwell’s use of the New Model Army.

Return to the immediate context

While it is true that President Washington’s first annual message to Congress advocated legislative steps to ready an effective standing army along with steps to give the national government substantial control over state militias, his audience did not consist only of federalists. The Congress continued to feature a small contingent of anti-federalists wary of centralized power–the same group responsible for suggesting versions of the Second Amendment much more explicit in establishing an individual right to bear arms.

Washington gave a political speech, and in that speech he specifically says that a free people ought to bear arms. Washington did not need to make that point to advocate a strong national government hand in the national defense. He could have done that without mentioning that a free people ought to bear arms. The phrase fulfills one central purpose: It served to assure his audience that he recognized the importance of an armed population to serve as a check on government tyranny.

Washington said it but he didn’t mean it!

Modern politicians have a reputation, deserved or not, for saying whatever is convenient whether they believe it or not. Is it possible that Washington offered an insincere reassurance to Congress?

Of course it’s possible. But we need to follow the evidence. If Washington made the statement, and he did, then we appropriately grant the benefit of the doubt for his sincerity unless we have good evidence suggesting otherwise. Again, that evidence is missing.

The experts get their say

Is there a case for viewing Washington as an opponent of Second Amendment gun rights in part established as a hedge against domestic tyranny?

A number of the experts interviewed, notably Mary V. Thompson of Washington’s Mount Vernon, provided biographical information that paints a picture of Washington as a strong proponent of a strong national government and a standing army. Washington held those views in common with the federalist-dominated Congress that passed 12 amendments to the Constitution of which ten turned into the Bill of Rights.

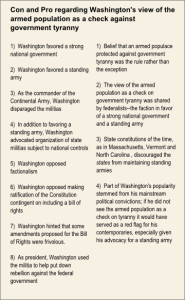

We think the first reason in the “Pro” column to the right outweighs all eight from the left column (click image for clearer view).

To conclude that Washington differed on the Second Amendment from the federalists we need more than the fact that he favored a strong national government and a standing army. Let’s consider what evidence we have, much of it summarized from expert interviews.

1) Washington favored a strong national government

2) Washington favored a standing army

3) As the commander of the Continental Army, Washington disparaged the militias

4) In addition to favoring a standing army, Washington advocated organization of state militias subject to national controls

5) Washington opposed factionalism

6) Washington opposed making ratification of the Constitution contingent on including a bill of rights

7) Washington hinted that some amendments proposed for the Bill of Rights were frivolous.

8) As president, Washington used the militia to help put down rebellion against the federal government

As a matter of logic, none of the listed reasons contradicts a belief that an armed population serves as a bulwark against domestic tyranny. We’ll look at the reasons in turn, considering whether they collectively provide the evidence to swing us toward the view that Washington broke with Hamilton and Madison on the role of armed citizens.

As Hamilton and Madison both favored a strong national government as well as a standing army we will take it as given that the first two points fail to make the case.

Washington disparaged the militias

As commander of the Continental Army, Washington found himself in competition with the militias for soldiers and supplies. When commanding militia troops he found their preparation lacking. Washington finished the war convinced that militias were unsuitable as the sole national defense and that the new nation would need some type of standing army.

Regardless of the depth of Washington’s conviction that militias were insufficient for national defense, that conviction again fails to contradict the simultaneous belief that an armed population would serve to protect a people’s liberty from a government’s swing toward tyranny. Washington’s harsh words about militias give us the thinnest of evidences that he did not view the Second Amendment and armed citizens as protection against tyranny.

Washington advocated organization of state militias subject to national controls

Consulted on the need for a standing army, Washington proposed a small standing army supplemented with state militias following the command and regulations of the federal government. Washington’s recommendation was likely more respectful of the role of the states than he might have preferred. Still, in the context of national defense Washington’s view was wise and understandable. It was also consistent with a role for armed citizens protecting liberty from government tyranny while also filling a role in the national defense.

Washington opposed factionalism

“Washington would have agreed with Hamilton that the threat to individual liberty was going to come from disunity, which would likely result in conflicts between the various states or groups of states,” Mary V. Thompson said. A strong central government would forestall that possibility, she added.

Thompson’s point is inarguable, yet it gives us no reason for thinking Washington disagreed with Hamilton that an armed civilian population still served as a check on the potential tyranny that would result if power in the federal government was usurped. The framers’ concern seems like an issue of achieving a balance of means and ends rather than favoring one means to the exclusion of another.

Washington opposed making ratification of the Constitution contingent on including a bill of rights

As a proponent of a strong central government, Washington favored the speedy acceptance of the Constitution as a matter of national security. Washington’s preference on this issue has no obvious importance to his view of citizens’ gun rights as a check on government tyranny. Washington believed that once the Constitution was ratified then Congress and the people could add amendments later. History proved his belief.

Washington hinted that some amendments proposed for the Bill of Rights were unimportant.

In correspondence with James Madison in May 1789, Washington wrote:

As far as a momentary consideration has enabled me to judge, I see nothing exceptionable in the proposed amendments [to the Constitution, i.e. the Bill of Rights]. Some of them, in my opinion, are importantly necessary, others, though in themselves (in my conception) not very essential, are necessary to quiet the fears of some respectable characters and well meaning Men. Upon the whole, therefore, not foreseeing any evil consequences that can result from their adoption, they have my wishes for a favourable [sic] reception in both houses.

Washington was elected president earlier in 1789 and supported the development of a bill of rights since some states had ratified the Constitution based on that expectation. Madison had taken the lead in listing the proposed amendments. As he submitted his list of 17 amendments to Congress on June 8, 1789, after this letter from Washington, we may suppose Madison gave Washington a preview of the list.

Amendments that failed to pass Congress were likely of lesser importance in Washington’s eyes considering the federalist majorities in both houses.

In any case, Washington’s letter does little more than tell us that Washington found the Second Amendment in its original proposed form somewhere between “importantly necessary” and “not very essential” while at the same time acceptable to him either way. The equivocal quotation serves poorly either as Washington’s condemnation or endorsement of individual gun rights.

As president, Washington used the militia to help put down rebellion against the federal government

Another of Thompson’s inarguable points drew on Washington’s use of militias to put down domestic insurrection. Of course, those who advocate gun ownership as a hedge against government tyranny do not necessarily consider every unpleasant action of the government an act of tyranny.

Thompson makes that distinction, in effect:

For those who might argue that Washington had done something similar by revolting against British taxes in the Revolution, I would counter with his belief that under the British system, the Americans had no say in whether they were taxed or not (“No taxation without representation”), but that under the new government formed by the states based on the Constitution, they did have a say in their government, through their representatives in the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Put another way, taxation without representation is tyranny while taxation with representation is not necessarily tyranny.

So long as we are able to distinguish between tyrannical government and non-tyrannical government, we can distinguish in principle between the armed citizen resisting tyrannical government and simply engaging in insurrection.

The cumulative case

The cumulative case that Washington did not see the armed citizen as a hedge against tyrannical government rests on nearly nothing. The nature of the evidence makes it likely that Washington viewed the role of the armed citizen in pretty much the same way as did the other Americans of his time. The armed citizen was the natural defense for a state or nation governed by the people. The people require a defense of their natural rights from external threats as well as from a domestic government turned to tyranny.

Is the right to bear arms individual, collective or reserved to the states?

The right to bear arms was widely and manifestly acknowledged as a check on the tyranny of government in addition to its role in defending from outside aggression. The scope of the right to bear arms makes up the modern debate and could easily color interpretations of Rep. Gohmert’s statement of a common motivation with George Washington.

We will not attempt to settle this dispute. We’ll stick with describing it.

An individual right to bear arms?

Proponents of the individual right to bear arms believe the right extends to a natural right to self defense. They argue that the wording of the Second Amendment specifically recognizes a right of “the people” to bear arms.

Critics counter that if the right to bear arms counts as an individual right then it follows that the individual also has the right to resist the government. They argue that the preamble to the Second Amendment fixes the right to bear arms within the framework of an organized and well-regulated militia.

A corporate right to bear arms?

Advocates of a corporate right to bear arms also emphasize that the Second Amendment recognizes a right of “the people” to bear arms. But they restrict that right to the function of a militia and its role in providing for the common defense, in part based on the preamble of the Second Amendment.

A state right to an armed militia?

Advocates of the right of a state to an armed militia take the Second Amendment to preserve against federal power the right to a state militia. States are thus free under the Second Amendment to restrict the right to bear arms within their own borders.

Which of the three views did George Washington hold?

It’s unlikely we have enough material from Washington or his contemporaries to make a definitive judgment about Washington’s view of the specifics of the right to bear arms. Today’s disagreement keeps in dispute even the views of those framers who made relatively specific statements on the issue of the Second Amendment.

To whatever extent Rep. Gohmert tried to enlist Washington as a proponent of an individual right to bear arms, that effort is certainly questionable. We believe that the experts who dismissed the legitimacy of Gohmert’s statement probably viewed it in that light.

The limits on the power to police rhetoric

Given that Gohmert can’t legitimately enlist Washington as a proponent of an individual right to bear semi-automatic weapons, what defense does he have against those who condemn his rhetoric?

Gohmert can use the same reasoning one might use to justify the modern extent of freedom of speech in light of the framers’ defense of free speech.

It’s possible that every one of the framers would find certain of pornographer Larry Flynt‘s publications obscene to the point of permitting a government ban. Despite that, it’s fair to take statements from the framers in support of free speech to defend the speech of those, like Flynt, who push the limits of free speech.

Gohmert, by analogy, is likewise free to point to Washington’s likely reason for saying a free people ought to be armed to support his own application of gun rights based on similar reasoning.

Probably nobody knows how Washington would specifically view today’s gun rights issue. For the fact checker there’s one clear issue: Did Washington see the Second Amendment as a check on government tyranny? He very likely did. Secondarily, did Gohmert try to make it look like Washington favored an individual right to bear arms? Perhaps a case can be made that Gohmert tried to give that impression. We don’t see it, but we reject that would-be connection on behalf of those who see it in Gohmert’s rhetoric.

Conclusion

The Second Amendment was instituted, at least in part, as a check on government tyranny. Washington was very likely to have viewed it that way, and his reference during his annual address to the people having arms almost certainly reflected that. It’s reasonable for advocates of an individual right to bear arms to justify the motivations behind their modern application of the Second Amendment by finding parallel motivations among the framers.

Correction and update Nov. 20, 2013: A reader noticed some broken links on this page. We’ve corrected some of the problems, most of which result from host pages changing their link structure and the like. We also corrected our misspelling of Richard C. Stazesky’s last name. Our apologies to Mr. Stazesky.

Correction and update Aug. 14, 2016: Reader Kate Hayes pointed out we put the wrong date on Thomas Jefferson’s letter to Col. David Humphries. We had 1889, when the right date was 1789. The date was fixed and a reference to the letter was added to the end of our “Works Consulted” section.

Works Consulted

(List updated on Feb. 18, 2013, adding list of interviews)

Owen, Sue. “Louie Gohmert Says George Washington Said a Free People Should Be Armed to Guard against Government Tyranny.” PolitiFact Texas. PolitiFact/Austin American-Statesman, 3 Jan. 2013. Web. 08 Jan. 2013.

Gohmert, Louie. “Connecticut School Shooting Reignites Gun Control Debate.” Interview by Chris Wallace. Fox News. FOX News Network, 16 Dec. 2012. Web. 08 Jan. 2013

Washington, George. “Annual Message to Congress, January 8, 1790.” Speech. Presidential Addresses and Messages. University of South Florida. Web. 09 Jan. 2013.

“Ron Chernow Author, “Washington: A Life” (part Two).” Q & A. National Cable Satellite Corporation, 10 Oct. 2010. Web. 09 Jan. 2013.

“John T. Woolley.” Department of Political Science. UC Santa Barbara, n.d. Web. 09 Jan. 2013.

Anderfuren, Marian. “Crackel Retires; Lengel Takes Helm at U.Va.’s Papers of George Washington.” UVA Today. University of Virginia, 27 Sept. 2010. Web. 09 Jan. 2013.

Uviller, H. Richard., and William G. Merkel. “Madisonian Structuralism.” The Militia and the Right to Arms, Or, How the Second Amendment Fell Silent. Durham: Duke UP, 2002. 89. Google Books. Google. Web. 10 Jan. 2013.

Hamilton, Alexander. “The Federalist No. 8.” The Federalist #8. The Constitution Society, n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2013.

Cress, Lawrence Delbert. “An Armed Community: The Origins and Meaning of the Right to Bear Arms.” Journal of American History 71.1 (1984): n. pag. Print.

Kates, Don B., Jr. “The Second Amendment: A Dialogue.” Law and Contemporary Problems 49.1 (1986): 143-45. Print.

Halbrook, Stephen P. “What the Framers Intended: A Linguistic Analysis of the Right to “Bear Arms”.” Law and Contemporary Problems 49.1 (1986): 151-62.

Gardiner, Richard E. “To Preserve Liberty-A Look at the Right to Keep and Bear Arms.” N. Ky. L. Rev. 10 (1982): 63.

Konig, David Thomas. “The Second Amendment: A Missing Transatlantic Context for the Historical Meaning of “the Right of the People to Keep and Bear Arms”.” Law and History Review 22.01 (2004): 119-159.

Malcolm, Joyce Lee. “Supreme Court and the Uses of History: District of Columbia v. Heller, The.” UCLA L. Rev. 56 (2008): 1377.

Malcolm, Joyce Lee. To Keep and Bear Arms: The Origins of an Anglo-American Right. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1994. Google Books. Google. Web. 11 Jan. 2013.

Malcolm, Joyce Lee. “Right of the People to Keep and Bear Arms: The Common Law Tradition, The.” Hastings Const. LQ 10 (1982): 285.

Washington, George. “Article 1, Section 8, Clause 12: George Washington, Sentiments on a Peace Establishment.” The Founders’ Constitution. Vol. 3. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1987. N. pag.

Washington, Geo. “George Washington to George Mason 5 April 1769.” Letter to George Mason. 5 Apr. 1769. Papers of George Washington. University of Virginia, n.d. Web. 10 Jan. 2013.

Bradley, Harold W. “The Political Thinking of George Washington.” The Journal of Southern History (1945): 473-74. Print.

Headley, Joel Tyler. “Elected Commander in Chief.” George Washington. Vol. 1. New York: Baker & Scribner, 1847. 25. Google Books. Google. Web. 11 Jan. 2013.

Bowie, Edward L. “An Eternal Constant: The Influence of Political Ideology on American Defense Policy 1783-1800 and 1989-1994.” Army Command and General Staff Coll Fort Leavenworth KS, 1994.

Stazesky, Richard C. “George Washington, Genius in Leadership.” Papers of George Washington. University of Virginia, n.d. Web. 10 Jan. 2013.

“George Washington.” Colonial Williamsburg. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, n.d. Web. 10 Jan. 2013.

Stearns, Cliff. “THE HERITAGE OF OUR RIGHT TO BEAR ARMS.” St. Louis University Public Law Review 18.1 (1999): 13. Saf.org. The Second Amendment Foundation Online. Web. 15 Jan. 2013.

“Bill of Rights.” The James Madison Research Library and Information Center. MadisonBrigade.com, n.d. Web. 24 Jan. 2013.

Lund, Nelson. “A Primer on the Constitutional Right to Keep and Bear Arms.” A Primer on the Constitutional Right to Keep and Bear Arms. Virginia Institute for Public Policy, June 2002. Web. 10 Jan. 2013.

Carp, E. Wayne. To starve the army at pleasure: Continental Army administration and American political culture, 1775-1783. University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Hart, Gary. The Minuteman: Restoring an Army of the People. Simon and Schuster, 1998.

Dunlap Jr, Charles J. “Revolt of the Masses: Armed Civilians and the Insurrectionary Theory of the Second Amendment.” Tenn. L. Rev. 62 (1994): 643.

Lengel, Edward G. This Glorious Struggle: George Washington’s Revolutionary War Letters. Smithsonian, 2008.

Shalhope, Robert E. “The Ideological Origins of the Second Amendment.” The Journal of American History 69.3 (1982): 599-614.

Weatherup, Roy G. “Standing Armies and Armed Citizens: An Historical Analysis of the Second Amendment.” J. on Firearms & Pub. Pol’y 1 (1988): 63.

Vandercoy, David E. “History of the Second Amendment, The.” Val. UL Rev. 28 (1993): 1007.

Williams, David C. “Militia Movement and Second Amendment Revolution: Conjuring with the People.” Cornell L. Rev. 81 (1995): 879.

Konig, David. “Why the Second Amendment Has a Preamble: Original Public Meaning and the Political Culture of Written Constitutions in Revolutionary America.” UCLA Law Review 56.1295 (2009).

Cramer, Clayton, Nicholas Johnson, and George Mocsary. “‘This Right is Not Allowed by Governments that are Afraid of the People’: The Public Meaning of the Second Amendment When the Fourteenth Amendment Was Ratified.” George Mason Law Review 17.3 (2010): 823-862.

Kates, Don B. “Modern Historiography of the Second Amendment, A.” UCLA L. Rev. 56 (2008): 1211.

Moncure Jr, Thomas M. “Who is the Militia-The Virginia Ratification Convention and the Right to Bear Arms.” Lincoln L. Rev. 19 (1990): 1.

Cornell, Saul. “Mobs, Militias, and Magistrates: Popular Constitutionalism and the Whiskey Rebellion.” Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 81 (2006): 883.

Mocsary, George A. “Explaining Away the Obvious: The Infeasibility of Characterizing the Second Amendment as a Nonindividual Right.” Fordham L. Rev. 76 (2007): 2113.

Amar, Akhil Reed. “Some New World Lessons for the Old World.” The University of Chicago Law Review (1991): 483-510.

Shalhope, Robert E. “The Armed Citizen in the Early Republic.” Law and Contemporary Problems 49.1 (1986): 125-141.

Henigan, Dennis A. “Arms, Anarchy and the Second Amendment.” Val. UL Rev. 26 (1991): 107.

Halbrook, Stephen P. “Right to Bear Arms in the First State Bills of Rights: Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Vermont, and Massachusetts, The.” Vt. L. Rev. 10 (1985): 255. (alt. link)

Williams, David C. “Civic Republicanism and the Citizen Militia: The Terrifying Second Amendment.” Yale Lj 101 (1991): 551.

Persson, Torsten, Gerard Roland, and Guido Tabellini. “Separation of powers and accountability: Towards a formal approach to comparative politics.” (1996).

Hoadley, John F. “The emergence of political parties in Congress, 1789-1803.” The American Political Science Review (1980): 757-779.

Redish, Martin H., and Elizabeth J. Cisar. “” If Angels Were to Govern”: The Need for Pragmatic Formalism in Separation of Powers Theory.” Duke Law Journal (1991): 449-506.

Sundquist, James L. “Needed: A political theory for the new era of coalition government in the United States.” Political Science Quarterly (1988): 613-635.

Ervin Jr, Sam J. “Separation of Powers: Judicial Independence.” Law & Contemp. Probs. 35 (1970): 108.

“A History of the Bill of Rights.” ACLU of Florida. ACLU of Florida, n.d. Web. 05 Feb. 2013.

Thompson, Mary. “Interview 1 with Historian Mary Thompson.” E-mail interview. Jan. 2013.

Lengel, Edward G. “Interview 1 with Historian Edward G. Lengel.” E-mail interview. Jan. 2013.

Konig, David T. “Interview 1 with Professor David T. Konig.” E-mail interview. Jan. 2013.

Malcolm, Joyce Lee. “Interview 1 with Professor Joyce Lee Malcolm.” E-mail interview. 16 Jan. 2013.

Added Aug. 14, 2016:

From Thomas Jefferson to David Humphreys, 18 March 1789.

One of the things that are not mentioned is the concept of ” an anachronism “. The United States has an ARMY, it has a NAVY, it has an AIR FORCE ,and it has a MARINE FORCE. The needs that existed way back when George Washington was Commander – ib – Chief no longer EXIST. What does exist are nut jobs who present a danger to defenseless first graders who can get wiped out in a few minutes. That is why the 2nd Amendment is no longer a relevant argument. Just because the 2nd Amendment had its place and time back in 1791 doesn’t mean it should be with us today.

Joseph Holohan wrote:

Actually that is mentioned implicitly, via our observation that we cannot deduce Washington’s attitude toward the gun issue today based on his views on the issue in the 18th century. But we can use what we know about the situation then plus what Washington said and wrote to estimate what he thought about the issue back then. And that’s not anachronistic.

That’s not obviously true, is it? Were the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines able to protect the citizens killed and injured in San Bernardino? If the armed forces plus the police served as a foolproof defense of the people, then the 2nd Amendment would lose its historical justification–the local and immediate defense of the people. The rise of terrorism may in fact refresh arguments for the need for the 2nd Amendment. Armed citizens might have prevented much of the loss of innocent life in San Bernardino and Paris. A trained local militia perhaps more so.

Thanks for reading and commenting.

The future of our country is uncertain, it is the right of the populace to be armed versus possible government tyranny. Look at all the “modern” societies that have perpetrated evil during the last century. Germany is a prime example WW2 era, many were stripped of their weapons, and defenseless against their governments tyranny. I am talking about law abiding citizens have the right to defend themselves vs not only a tyrannical government, but also the right to defend my family, as police can not stop a home invasion robbery, but a well armed citizen can.

If, indeed, as it appears, the 2nd Amendment’s aim was to be a hedge against possible government tyranny, then, today, we must allow for a citizenry that possesses F16s, tanks, submarines, etc. These would be the evolutionary equivalents necessary to protect US from the Tyrant. Maybe we should evolve beyond the 2nd Amendment, instead.

“Maybe we should evolve beyond the 2nd Amendment, instead.”

Perhaps. But it seems reasonable to object to the proposal unless we have some assurance that governments have evolved past tyranny.

Everyone here is commenting as if our only threats were external or only from our own government. Foreign armies are not behind school or local shootings. These are, as some keep saying, “nut jobs” within our own society or religious zealotry. So forget armies, etc. Let’s look closer to home. Who, specifically, is responsible for your protection and the protection of your family? If you believe the police are, you need to read “Gonzalez v. Castle Rock” (among others) and the SCOTUS decision. Police carry guns to protect themselves when apprehending suspected or known felons, not to protect the individual citizen (even if they happen to be close enough to do so, and I have _never_ seen a police cruiser pass my house). My guns allow myself or my wife to protect our family from “nut jobs” and bad guys who have only contempt for our laws or have socially unacceptable motivations and threaten us. It’s time we taught our children proper gun handling in our schools just as we teach sex education or driver education. We should be arming our citizens, not disarming them.

David A. Bandel wrote: “Everyone here is commenting as if our only threats were external or only from our own government.”

Right, but that’s only natural since the fact check addresses the denial, promulgated by PolitiFact Texas, that George Washington viewed the 2nd amendment as a hedge against the tyranny of the national government. At the same time it’s quite true that the right to arms in England was promoted as the defense of the population as well as a defense of the realm.

You have Thomas Jefferson making a reply in 1889. I think you meant 1789. Other than that, your article was very informative.

Kate Hayes, thanks for your observation. Something does sound amiss, so we’ll see about making sure we get the right date in the article. Thanks for reading!

The Washington quote is spurious:

http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/spurious-quotations/

Perry Logan,

Whether you read our article or not, we thank you for visiting. Our article does not rely on the version of the quotation your link identifies as spurious. Our article relies on the version straight from Washington’s annual address, which the site you linked affirms as authentic.

**This quote is partially accurate as the beginning section is taken from Washington’s First Annual Message to Congress on the State of the Union. However, the quote is then manipulated into a differing context and the remaining text is inaccurate. Here is the actual text from Washington’s speech:

“A free people ought not only to be armed, but disciplined; to which end a uniform and well-digested plan is requisite; and their safety and interest require that they should promote such manufactories as tend to render them independent of others for essential, particularly military, supplies.”**

http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/spurious-quotations/

Cheers.

A key part of the broader historical context for the words of the founding generation is the universality of compulsory service in the organized militia of the states. It was a very different situation than that of the present day, when we know only of the unorganized militia. But in 1785, the whole body of the people-virtually all men between the ages of 18-45-had to enroll in the organized militia of their state, appear for periodic drill and be subject to active service under state authority.

The state militias were not exclusive. There remained local “unorganized” militias and locally organized ones as well.

http://academic.udayton.edu/Health/syllabi/Bioterrorism/8Military/milita01.htm

Why is this a key part of the broader historical context, specifically?